![]() Passion Category Winner in the 2012 WanderWomen Write Travel Writing Contest!

Passion Category Winner in the 2012 WanderWomen Write Travel Writing Contest!

By Madeline Felix

MRS. THU, the dean of the college English department where I was teaching on a year-long fellowship in Vietnam, told me that living alone in her country would be good for me because I would learn to cook, clean and take care of myself. She said this would help me find a husband.

MRS. THU, the dean of the college English department where I was teaching on a year-long fellowship in Vietnam, told me that living alone in her country would be good for me because I would learn to cook, clean and take care of myself. She said this would help me find a husband.

Mrs. Thu was not alone in her concern for my marital status. After a few weeks, I had noticed that, “Are you married?” was often the first question posed by the Vietnamese. When I asked Mrs. Thu why this was, she explained with a sly grin, “People are curious about you because you are so strange. They want to socialize and know you!”

After I would tell people that I wasn’t married, they would immediately ask, “Do you have a lover?” In Vietnamese, the term for boyfriend or girlfriend is “ngÆ°á»i yêu,” which translates to “love person.” I secretly relished being asked this question because for the first time in my life, I did.

We had met over a bowl of calamari at a friend’s birthday party in New York City two months before I left the United States; his dark good looks and goofy charm left me unable to stop popping fried squid into my mouth. When I told him that first night that I was soon moving to Vietnam, he replied, “Are you kidding? What will that do for our relationship?”

I knew he was joking, but as soon as the words came out of his mouth I wanted him to be serious. Two months later, sitting in a K-Mart parking lot days before I left, I told him I loved him.

WHEN I first arrived at Hải DÆ°Æ¡ng College with Mrs. Thu, I was greeted at the rusty metal school gates by at least a dozen men–various teachers and deans all eager to carry my luggage. They moved quickly, like a hive of worker bees, while I walked in the middle of their swarm. We crossed the concrete Soviet-era campus to my small apartment in one of the many rectangular brick and mortar buildings. When the men had set all of my things on the floor of my bedroom, they stood, military-like, in a line on the far side, silently staring at me. Eventually, Mrs. Thu said something in Vietnamese, and then they all lined up to shake my hand before disappearing as quickly as they’d descended.

It wasn’t until the next day that I met other women: English teachers who were Vietnamese and just a few years older than me. The more I got to know them, the more I thought of them as the cool girls in high school. I’d walk in on them gossiping with each other in the English office, their pin-straight black hair swinging as their heads moved to the rhythm of their quick-shot Vietnamese. When they saw me they’d smile and switch to their slow and careful English.

From the beginning, we talked mostly about family and relationships; it was one thing we had in common. I quickly learned that many of them were married with one or two children. They learned about my “Love Person” and began asking about him every time they saw me. As they introduced me to their friends, family, and other faculty, I’d always hear the words “ngÆ°á»i yêu.” Having a Love Person was soon part of my definition.

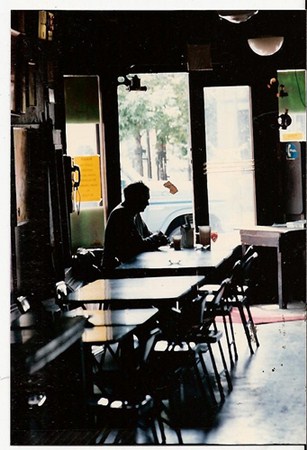

I LIKED to think of him sitting alone at a bar in Manhattan, drinking Scotch and bemoaning the woman who’d left him for Asia. I don’t think he really did that. Sometimes when we talked, the nebulousness of our relationship would feel heavy, like a fat man walking an 8,000 mile tightrope between us. We hadn’t discussed what our status would be when I was away. We had simply said we would try to make it work, whatever “it” was.

I LIKED to think of him sitting alone at a bar in Manhattan, drinking Scotch and bemoaning the woman who’d left him for Asia. I don’t think he really did that. Sometimes when we talked, the nebulousness of our relationship would feel heavy, like a fat man walking an 8,000 mile tightrope between us. We hadn’t discussed what our status would be when I was away. We had simply said we would try to make it work, whatever “it” was.

Now that I was gone for a year, what were we doing? How would we make it? I was afraid he’d forget me. It would pain me to turn off my computer as I approached the early hours of the morning in Vietnam. I couldn’t stop thinking about how it was afternoon in New York. What is he doing? I wondered. Will I hear from him later today?

My computer became a nightly addiction, and if the power or Internet went out–as it often did–I’d feel like something was being ripped away from me.

Before long, I found myself staying alone in my room during the day when I wasn’t working. I didn’t know how to talk to anyone, even the women, about my loneliness. I would scurry between my apartment, the English office, and the classrooms, trying to avoid attention.

One day in the English office, bent over my lesson plans, I sat across from a young teacher named Thanh who was pregnant. I knew that she was smart and serious, but we had never had a real conversation. I looked up when I sensed her staring.

“Madeline,” she said, “I think you are very brave to come here and leave everyone you know and love. When I was at college I lived away from my boyfriend and family, and I felt like I would explode sometimes. I think you feel that way, too.”

Blood rushed to my cheeks and I was afraid that if I tried to speak my voice would crack. I nodded and gave a brief smile, wondering if my feelings were so obvious. That was exactly how I felt: like I would explode.

The Love Person knew I was struggling, but I was afraid he would be freaked out if I told him just how much. I already felt him recoil sometimes when I couldn’t hide the panicked need for him in my voice. I knew if I didn’t want to drive him away and drive myself crazy, I needed to find another way to cope and truly be where I was.

To help me sleep at night, I began to self-medicate with a cocktail of two Benadryl and a glass of red wine from Da Lat, a mountainous city in the South. I forced myself to turn off my computer overnight.

During the days, I made it a rule that I had to leave campus at least once. It could be a twenty-minute bike ride, or hours drinking cà phê sữa đá–the delicious espresso-like coffee served with sweet and condensed milk and ice–while reading in a cafe. I just had to get out.

During the days, I made it a rule that I had to leave campus at least once. It could be a twenty-minute bike ride, or hours drinking cà phê sữa đá–the delicious espresso-like coffee served with sweet and condensed milk and ice–while reading in a cafe. I just had to get out.

I had been living on noodles and crackers, so I asked Mrs. Thu to take me to the market to buy chicken, vegetables and other fresh foods. Under a roof of blue and orange tarps lashed to bamboo poles, Mrs. Thu showed me how to carefully inspect the piles of produce and the slabs of meat and poultry brought in by women from the surrounding countryside. All around us I heard women bartering, women gossiping, women fighting over customers. I was surprised to feel a sense of calm and belonging in the flurry of female activity. After that first trip with Mrs. Thu, I returned to the market every week.

I also started going for lunch at a nearby phá» restaurant owned by a woman named PhÆ°Æ¡ng Lan. With straight black hair down to her waist and a valence of bangs above her dark eyes, I thought she was one of the most beautiful women I’d ever seen. The restaurant was on the first floor of her house in an open room filled with low tables and small plastic chairs I’d only seen used by preschoolers in the United States. PhÆ°Æ¡ng Lan came to expect me a few times a week, and she would smile curiously when I arrived.

I started asking some of the women teachers to come out with me for lunch or coffee between classes. Sometimes they would decline, saying they needed to go home to their families. However, a teacher named Huyen would often agree. Huyen was 29-years-old and had a three-year-old daughter named Minh. She lived with her in-laws while her husband was stationed at an army base in the South. She always asked me about the Love Person; I always asked her about her husband, Trieu. She told me not to laugh at her, but sometimes she cried missing him.

I said, “Oh God, I cry everyday!” and we both laughed.

The first day Huyen and I went out for phá» together, PhÆ°Æ¡ng Lan rushed over and linked my arm with hers as she started speaking to Huyen in Vietnamese. Huyen told me that PhÆ°Æ¡ng Lan said she was glad I had a friend.

As months passed I also fell into a routine with the Love Person. We would talk once or twice a week on Skype and email or text every few days. Sometimes it didn’t feel like we were 8,000 miles apart. We’d be Skyping, and he’d take his laptop into the kitchen so we could talk while he cooked spaghetti, as if I had just hopped up onto the counter to sit and chat. It seemed almost normal.

As months passed I also fell into a routine with the Love Person. We would talk once or twice a week on Skype and email or text every few days. Sometimes it didn’t feel like we were 8,000 miles apart. We’d be Skyping, and he’d take his laptop into the kitchen so we could talk while he cooked spaghetti, as if I had just hopped up onto the counter to sit and chat. It seemed almost normal.

Meanwhile, I kept myself busy with my students and by spending more time with the women. One day I walked into the English office to find Mrs. Thu playfully waddling around while the other teachers laughed.

“Madeline!” One of them said when she saw me.

“We are saying Thanh looks like a turtle because she is so pregnant!”

Thanh didn’t look like a turtle, per se, but she did look like an anatomical impossibility. Her body was still incredibly tiny, but her belly appeared to be carrying a toddler, not a baby. Mrs. Thu came over and put her arm around me.

“I wonder what Madeline will look like when she will have a baby. Like a turtle, too?”

A year earlier and I would’ve been terrified if someone said something like that to me. But with the women it felt natural, like something I’d always wanted.

When I went to visit Thanh a few days after she had given birth, she was sitting on a low wooden bed wearing a pale pink pajama set and cradling her baby boy. I could not remember the last time I had seen a baby so small, so close. She asked me if I wanted to hold him, and as he rested in my arms, I kept thinking, I’m holding a baby. My friend’s baby. I have a friend who has a baby. I am like a grown-up woman.

After the baby fell asleep, Thanh and I talked quietly. She had a very devoted husband, and the other women would sometimes tease her because he would clean the house and cook for her. Thanh was curious about what things were like for couples in America.

“I like a modern relationship between a man and woman,” she said in an almost conspiratorial tone. I liked that, too, I replied, unsure of what “a modern relationship” meant anymore. I used to think it meant I could do whatever I wanted and only worry about myself. Now I knew it was not so easy. Thanh asked if I thought I would get married and have children when I went back to America.

“I like a modern relationship between a man and woman,” she said in an almost conspiratorial tone. I liked that, too, I replied, unsure of what “a modern relationship” meant anymore. I used to think it meant I could do whatever I wanted and only worry about myself. Now I knew it was not so easy. Thanh asked if I thought I would get married and have children when I went back to America.

I replied, “Who knows? We’ll see.”

But I knew I wanted what Thanh had.

About a month before I left Vietnam, I got an email from the Love Person saying he was nervous about me coming home. I had been trying to pretend I didn’t feel him pulling away as my return date neared, but now I couldn’t ignore it. He said that he didn’t know how he’d feel after being apart for so long. He wanted us to be realistic. If we were going to have a real chance we were going to have to take it slow.

After I read the email, I called Huyen to ask if she would go to dinner with me that night. As I told her what he’d written, she put down her chopsticks and listened closely. When I finished, she paused before saying, “I don’t think you should worry. I think it will be OK. Whatever happens should happen.”

When the Love Person and I talked a few days later, I didn’t mention the email right away. It felt like we had to warm up first. I told him about the big theater project I had been working on with my students and the traditional wedding I had gone to with Huyen. As he asked me questions, I realized that I had told him so little about my day-to-day life in Vietnam. He didn’t know how much I loved my students, or how close I had become with the women teachers. When we talked, I had always wanted to know about his life in New York, or to discuss our plans for the future.

I told him I agreed we should take things slow when I got back. He said he wanted to really give us a shot. Before we hung up, he said, “I do love you, Mad.”

He always said it, but he so rarely had said it first.

A month later, as I hauled my luggage away from baggage claim at JFK airport, I saw him standing by the gate. There was something about the look on his face: nervous and tired. Then there was the awkward shift of his feet and our near-miss kiss as I went up on my toes to reach him and my heavy backpack threw me off-balance. After we loaded my things into his car and I slid into the passenger seat next to him, I didn’t know what to say. The unfamiliarity between us hung like a smokescreen.

We ended things for good about a month later. We had changed, both of us. I was scared to tell the Vietnamese women what had happened. I was worried they’d be disappointed in me or think it was a sign of feminine weakness that I’d lost him.

For my birthday, they’d given me a ceramic rice wine carafe that was shaped like two ducks.

“A traditional wedding gift!” They said smiling.

I knew what their expectation was. When I finally found the courage to email them, they replied right away, saying, “It’s good you’re not with him if it was not right anymore.” And, “You are strong and intelligent and beautiful. You will be fine.”

I knew what their expectation was. When I finally found the courage to email them, they replied right away, saying, “It’s good you’re not with him if it was not right anymore.” And, “You are strong and intelligent and beautiful. You will be fine.”

Of course, I can’t help but wonder what Vietnam would have been like for me had there been no Love Person. In some ways, I know it would have been easier. But I can’t ignore what he gave me. He was a link, a constant touchstone for connection. If there is one way to understand one another, it must be to talk about the people we love.

*****

Photo credits:

Motorbike Couple: Katina Rogers

Lonely Man in Bar: Robert Huffstutter

Vietnamese Iced Coffee: Soon Koon

Couple on Skype: rashida s. mar b.

Trendy Vietnamese Couple: Jeremy Weate

Vietnamese and American Women: aacc.asia