by Leslie Nevison

Some ironies are sweeter than others: When the pemangku blows into my face–a transfer of his protection and a long, slow, steady release of air as though he is deflating–his breath must carry the cold virus to which I succumb by the end of the week.

Some ironies are sweeter than others: When the pemangku blows into my face–a transfer of his protection and a long, slow, steady release of air as though he is deflating–his breath must carry the cold virus to which I succumb by the end of the week.

A pemangku is a lower rank of Hindu priest who, along with other traditional healers called balian, is as customarily consulted on Bali in times of illness and injury as a medical doctor is in the West. Balian also address problems beyond the scope of science. They locate stolen objects, or identify their thieves; they lift spells, predict weather, channel spirits, produce potions and charms, even paint pictures of the new car you desire most as a means of acquiring it. The pemangku I visit is popular with women who want minute particles of gold inserted under their facial skin, talismans that render them irresistible to prospective spouses or business investors. I admit that such enhancement sounds attractive, but the three days of prayer and meditation that are required for the pemangku to activate his gold “needles” is too long for me to wait. I have enough time–just under an hour–for him to empower a banana, which he has me eat, and his breath. Only the latter has any effect of which I am certain.

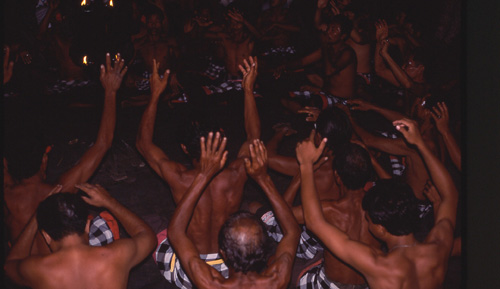

Throughout Southeast Asia, there survives the belief in a sentient nature and man’s reciprocal  relationship with it. The pemangku’s choice of banana as his mystically charged object is an example of this exchange, an animate product of the earth (and not coincidentally an important regional food crop) that is used ritually. Shamans–known as balian, bomoh or dukun in the Indonesian archipelago–are the intermediaries with the resident spirits of plants, animals, rivers, mountains and weather.

relationship with it. The pemangku’s choice of banana as his mystically charged object is an example of this exchange, an animate product of the earth (and not coincidentally an important regional food crop) that is used ritually. Shamans–known as balian, bomoh or dukun in the Indonesian archipelago–are the intermediaries with the resident spirits of plants, animals, rivers, mountains and weather.

They occupy a place apart and unseen that the Balinese call the niskala, which is of equal importance to the sekala, the visible world. The niskala isn’t necessarily malevolent, but it can be capricious, and so it and the balian who converse with it are treated reverentially. The beautifully-crafted tiny trays of palm leaves, flower petals, fruit, rice and incense left early morning and late afternoon on sidewalks, outside doorways, on altars, and dashboards of vehicles, are the gestures the Balinese make to the niskala spirits to ensure with them a peaceful coexistence. Any number and types of crises–accidents, crop failures, bankruptcies, or disease–are indicators of something wrong. Intervention is then required by balian, whose treatments aren’t as much cures as they are appropriate methods of atonement.

Local Crafts

For me, buyers and sellers of Balinese handicrafts are the niskala in tangible form. Their proliferation has contributed to my neglect of Bali. My last visit was over twelve years ago. Yet  even first-timers to Bali today depart transformed. I wonder if there isn’t some basis of truth to the idea of Bali as a spiritual sanctuary, just as the popular (and lucrative) concept of Bali as a paradise has its roots in the pretty landscape, and Bali as a place of enchantment reflects the magic that is actually practiced there by its balian. I have social obligations to friends living in Bali and decide to fulfill them while seeking out as many healers as my week-long visit allows.

even first-timers to Bali today depart transformed. I wonder if there isn’t some basis of truth to the idea of Bali as a spiritual sanctuary, just as the popular (and lucrative) concept of Bali as a paradise has its roots in the pretty landscape, and Bali as a place of enchantment reflects the magic that is actually practiced there by its balian. I have social obligations to friends living in Bali and decide to fulfill them while seeking out as many healers as my week-long visit allows.

It is easier to meet balian if I approach them as a patient. This means thinking of a complaint or ailment, but this isn’t difficult when so much can be improved by mystical intervention. Nor am I restricted to seeking the aid of only the Balinese. The island’s esoteric cosmology attracts and tolerates an international set of alternative therapy practitioners. These transplanted healers are easily drawn into discussion, less bound culturally to guard their beliefs and practices. Healing is to them part of a larger process of spiritual development, both personally and socially. (An argument may be that many expatriates have time and the financial security to devote to such pursuits.) While indigenous healers don’t question their island’s significance in a greater spiritual scheme, those who have adopted Bali are convinced of it. Says one expatriate, Bali shares it name with the evocative word in the Malay-Indonesian language which means to return: Kem-bali. Whether we are travelers or healers, perhaps none of us actually goes to Bali as much as we come home.

David, who came to Bali from Australia twenty years ago, has a theory that he shares with me over dinner in the serene setting of his moonlit garden. A stone sculpture of the Hindu god Ganesh is tucked away in an alcove in a perimeter wall, a Buddha in another, while in the middle of the yard are concentric circles of evenly spaced, enormous stones. David practices dowsing–a divination of earth energies–when he isn’t designing golf courses. The strange configuration of stones marks a “power-point,” or where dowsers believe that two kinds of energy lines intersect. Found all over the globe by members of the vast fraternity of dowsers, Bali nevertheless has some of the world’s greatest number of these synergetic centers, places of exceptionally pure energy brought about by ideal conditions and capable of altering human consciousness and promoting enlightenment. David believes that early temple builders in Bali were aware of “power-points”, and chose not only to raise their buildings on them, but to construct them in alignment with others as well.

The Meaning

There is more to David’s idea of earth energies and Bali: The human body has an incorporeal mate, in which stretches from head to tailbone seven whirling vortices that ancient Hindus called chakras. Through these rapidly revolving wheels ethereal energy circulates and acts as a conduit to the universe, activating as it does our spiritual nature. The planet, a living form, has chakras too. David contends that Bali is one of them.

Another long-term Australian resident of Bali, and self-professed shaman, Anne believes that Bali is the earthly twin of the “power” chakra located in our solar plexus which governs physical and psychic energy, the emotions, and the metabolism of such organs as the liver and spleen. Yellow, the color associated with the power chakra, figures prominently in Balinese rituals. (Before I could receive the pemangku’s magical breath, I tied a yellow scarf around my waist.) Even the geographical shape of Bali, Anne proposes, looks like a human liver. It is difficult to dispute an elder’s opinion. Anne claims to be an entity two million years old.

Another long-term Australian resident of Bali, and self-professed shaman, Anne believes that Bali is the earthly twin of the “power” chakra located in our solar plexus which governs physical and psychic energy, the emotions, and the metabolism of such organs as the liver and spleen. Yellow, the color associated with the power chakra, figures prominently in Balinese rituals. (Before I could receive the pemangku’s magical breath, I tied a yellow scarf around my waist.) Even the geographical shape of Bali, Anne proposes, looks like a human liver. It is difficult to dispute an elder’s opinion. Anne claims to be an entity two million years old.

Philosopher-ecologist-magician David Abrams, whose book The Spell of the Sensuous is my guidebook of choice on this trip, contends that new-age shamans like Anne cannot duplicate the function of indigenous healers, which is to cure disease that is necessarily a manifestation of a grievance between a place-centered culture and their environment. Problems are therefore shifted but never solved. But Anne is optimistic, convinced in the interdependence of all existences where even the smallest acts of healing and compassion have an accumulative effect. That the polar ice caps are melting, she said with a seriousness that I enjoy–and an implication that the north and south poles are the planet’s base and crown chakras–is not a harbinger of doom but an indication of increasing amounts of energy they receive as the human race works towards spiritual evolution.

Anne surprises me with her stories of the people who come to Bali to pursue tutoring in the black arts, which is the subverted application of white, or good, magic. After my appointment with the pemangku of gold-dust fame, I learned that he invoked Ratu Gede, a deity with a frightening biography and the favored patron of black sorcerers. Ratu Gede has a temple dedicated to him on Nusa Penida, an island a short distance off Bali’s eastern coast, and considered by the Balinese as angker, or excessively full of evil. Sanur, David’s and Anne’s neighborhood and popular beach resort, has a reputation as where black magicians practice. The proximity of the two places may be a factor: Nusa Penida is visible from Sanur on a clear day; David thought an energy line might connect them. Another theory associates Sanur’s angker with painful historical events. It was the first settlement of Dutch colonizers, as well as where the Japanese first invaded Bali in World War II. This doesn’t explain, however, why Sanur had remained uninhabited prior to the Europeans arrival, considered haunted by the local population even then.

Anne surprises me with her stories of the people who come to Bali to pursue tutoring in the black arts, which is the subverted application of white, or good, magic. After my appointment with the pemangku of gold-dust fame, I learned that he invoked Ratu Gede, a deity with a frightening biography and the favored patron of black sorcerers. Ratu Gede has a temple dedicated to him on Nusa Penida, an island a short distance off Bali’s eastern coast, and considered by the Balinese as angker, or excessively full of evil. Sanur, David’s and Anne’s neighborhood and popular beach resort, has a reputation as where black magicians practice. The proximity of the two places may be a factor: Nusa Penida is visible from Sanur on a clear day; David thought an energy line might connect them. Another theory associates Sanur’s angker with painful historical events. It was the first settlement of Dutch colonizers, as well as where the Japanese first invaded Bali in World War II. This doesn’t explain, however, why Sanur had remained uninhabited prior to the Europeans arrival, considered haunted by the local population even then.

To the elderly healer, Ibu “Mother” Marlena, who was born and raised by her magician grandfather in Sanur, definitive reasons to fear Sanur aren’t as important as it is prudent to accept it. Ibu’s grandfather used to walk across the sea from Sanur to Penida to meditate at Ratu Gede’s temple. Like the pemangku, however, her grandfather was not a black magician. To what end Ratu Gede’s dangerous powers are utilized depends entirely upon the balian. White magic isn’t necessarily stronger than black because it is good. Nor can the most potent black magic fully overcome white for there are protective countermeasures that can be taken. In a sense, each exists only to stop the domination of the other, a relationship of diametrical but balanced opposites, like the sekala and niskala, and a potent symbol in the black-and-white checked sacred cloth that adorns Balinese deities.

I am introduced to Ibu Marlena in the town of Ubud, where I spend a few days after leaving Sanur. A grandmother in her sixties, she is the only balian willing to talk about black magic, a difficult person to find where the belief is strong enough that even the subject’s passing mention can attract the attention of a less than well-meaning sorcerer. In exchange for her candor, Ibu asks that I take her treatment, which means I strip naked and accept her painful massage.

While Ibu’s mother carried her, a village seer told the family that the baby would be special. As a youngster, Ibu’s neighbors came to her to ease their aches and pains; when her mother had a headache, she would place Ibu’s tiny hands against her forehead. Those therapeutic instruments now knead my flesh, unblocking the obstacles in the series of pathways that the Balinese believe extend throughout the body, conveying blood, life fluids and forces. Some of these, such as veins, tendons and nerves, the Balinese accept as scientific fact. Others are unknown to Western biology and are taken as a matter of faith. A troupe of accomplished women ply the massage trade along Bali’s beaches, but Ibu’s difference lies in the fact that her hands are endorsed by niskala-based powers, harnessed through prayer, meditation and offerings.

The Healer

The Healer

A note is delivered to me where I sit in the garden of my Ubud guesthouse, Ibu’s oils still sticky upon my skin. Arthur is sending his maid and her husband, Ketut and Wayan, to take me to a balian tulang or a setter of broken bones. “I’m sure that you will have an enlightening experience,” wrote Arthur. “He performed a miracle on me.” A year ago, Arthur was in a bad car accident. Many bones were so badly damaged that Western medical practitioners despaired of his total recovery. Then he sought treatment from the balian.

Arthur’s healer lives in a village at the foot of Mount Agung, Bali’s highest mountain at 3142 meters, and home to all her gods. His clinic is an open platform attached to his house, which is near to Besakih, one of Bali’s most sacred temples, visited by hundreds of pilgrims every day. It is a one-and-a-half hour drive from Ubud, covered in the chilled comfort of Wayan’s new sports utility vehicle and through a late afternoon suffused with yellow light.

We go first to the balian’s altar to leave our offerings and to light incense. A container of water, blessed by temple priests, is placed there among fresh flowers and fruits. Ketut scoops up a few inches in a jar, dips in a flower and holding the blossom elegantly between two fingers, sprinkles us each three times. She then dribbles water into my cupped hands and motions for me to drink. In final preparation, we insert a blossom behind our right ears as evidence of our purity.

When the balian emerges from his house, he also goes first to his altar and takes from there a glass bottle filled with thick, black oil. He has made this from plants collected on Mount Agung. It is imbued by his magical incantations. The healer is a handsome, middle-aged man with a serious smile. He offers no information about himself other than that his father and grandfather were bone healers. His brother practices it too. His first patient is a young boy who broke his arm several weeks earlier falling out of a coconut tree. The balian rubs his oil into the boy’s limb, which looks to be mending well.

When the balian emerges from his house, he also goes first to his altar and takes from there a glass bottle filled with thick, black oil. He has made this from plants collected on Mount Agung. It is imbued by his magical incantations. The healer is a handsome, middle-aged man with a serious smile. He offers no information about himself other than that his father and grandfather were bone healers. His brother practices it too. His first patient is a young boy who broke his arm several weeks earlier falling out of a coconut tree. The balian rubs his oil into the boy’s limb, which looks to be mending well.

It is then that a truck appears and five family members carefully lift from its open bed a man in obvious and great pain. There is no blood or sign of trauma from his motorcycle accident that morning, but someone holds up an X-ray to the light. The thighbone has separated; its severed ends lie neatly side by side. The balian studies the film at length and holds a quiet discussion with patient and family before kneeling by the injured leg.

The Balinese do go to hospitals and clinics as the X-ray attests. The family may have lacked the financial means for a leg cast for their son; the clinic may have been busy and the wait long. Perhaps harried doctors do not, and cannot, inspire the same confidence of which traditional healers are capable–who have, after all, more powerful connections. The balian would realign this broken bone, but cushion it in no other protective device than a crudely built box. His patient would then be transported up and down the mountain to him for frequent monitoring and applications of the special ointment, sessions always preceded by prayer and small acts of appeasement to the mystical forces whose involvement and continued involvement could not be discounted in the unfortunate event.

The balian grasps the broken leg and manipulates it, while the man’s brothers hold their sibling down, his face twisted and pale. I hear an unfamiliar grating noise.

The balian raises the leg again; the sound of shifting parted bones is less strange but no less horrible. If ritual for their son’s injury dispels this family’s fears, it raises the darkest of mine.

At the completion of Ibu’s massage, there had occurred an awkward moment when I was reluctant to enthusiastically endorse the transformations that she believed that I had undergone. The problem was mine. She had an outer room full of people wanting to see her, who presented her with faith as well as symptoms. I brought and gave nothing to healers of the “immense belief” that Arthur credits for his remarkable recovery from his car accident.

If the healing process fails, the diplomatic Balinese absolve healer or client of blame, attributing the cause to an incompatibility between them. But was this retribution in the form of the pemangku’s cold, the beginnings of which I can feel in my throat and chest?

To my great embarrassment, I feel faint and sink to my knees. An anxious Ketut takes my elbow and we return slowly to the car where Wayan waits for us. The balian never looks away from his patient’s broken leg. As we descend Mount Agung in silence, the outline of Nusa Penida Island shimmers in the distance.

*******

Canadian born Leslie attributes her wanderlust to her mother who took her to live in Europe as a teenager. She had her husband of 25 years first went overseas to live in 1990. They have since called seven countries home–Turkey, the Sultanate of Oman, Singapore (twice), Tanzania, Uzbekistan, Greece, and Congo-Brazzaville. Leslie has traveled through another thirty. Since 1996, she has written 40 travel articles for publication. In 2005, she started Mama Tembo Tours, wildlife and culture safaris to Tanzania for independent-minded individuals and small groups. Leslie says she became a solo traveler out of necessity, but quickly learned that going it alone has its distinct advantages.

Photo credits:

Leaf: Chris Walker Innerwealth

Bali fields: riza

Umbrella: riza

Buddha: Pimpmaster Jazz

by Beth Whitman