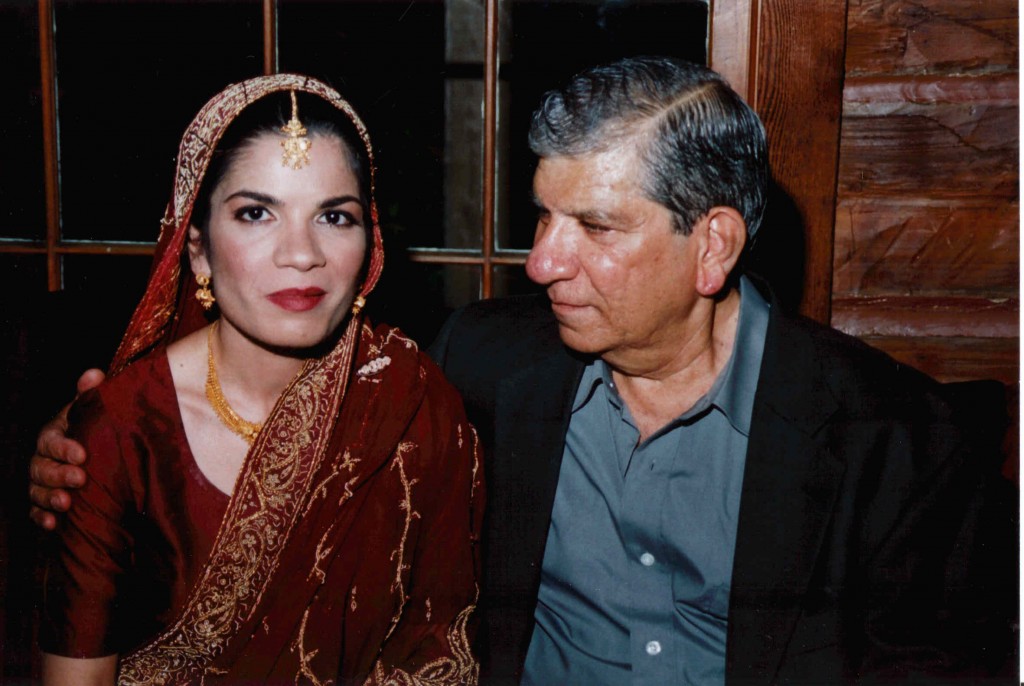

by Maliha Masood

“There are no crooners left in Karachi.”

“There are no crooners left in Karachi.”

I’m not sure if he means it literally. But then my father goes on to talk about the Binaca Hit Parade. It was a popular radio program in Pakistan when he was growing up. That’s where Abboo first heard Georgia Gibbs singing Seven Lonely Days. He sang that song more than any other. But he couldn’t pull off the woo woo woos, at least not as well as Sohrab Rustum, whose deep tenor baritone did justice to the chorus. They would be joined by Hatim, Asghar, Damian and soon the whole gang was in full performance, a bunch of brown faced, Karachi kids splayed across cultural idioms and mad about big band tunes. The show was aired at 8 a.m. and became their morning ritual before school. According to my Dad, he and his friends would all walk together to Saint Patrick’s, humming and whistling melodies from the day’s lineup.

It’s a city we can both call home, but across radically different generations and eras. My father came to Karachi as a mohajir, a Muslim migrant from India, a few years after partition when Pakistan emerged as a brand new nation-state. He was fifteen years old when he left his native Madras along with his parents and two younger sisters and boarded the SS Damra, a passenger liner that sailed between Bombay and Karachi.

Coming of age during the 1950’s and 60’s, my father was enamored with two things – music and the movies. It was in Karachi that Abboo witnessed the birth of Rock & Roll from Billy Haley and the Comets to Fats Domino, Little Richards and Elvis. It was in Karachi that he moonlighted as a jazz groupie, watching Dizzy Gillespie perform at the Palace Cinema in 1956, shortly followed by Jack Teagarden at the Rex Cinema Hall and then Arty Shaw. It was in Karachi that Abboo saw Marilyn Monroe in Niagra and River of No Return, Fellini’s La Dolce Vita, Hitchcock classics, Fred Astaire musicals and scores of Spaghetti Westerns.

A French Riviera by the Arabian Sea. A carefree, happening town exuding cosmopolitan cool. This was the Karachi of my Dad’s youth. Compared to all this, my Karachi was far less glamorous. Instead of Dizzy Gillespie, I was into Abba and the Bee Gees. It was in Karachi where I learned how to groove to Staying Alive. And listened to Cheap Trick and Fleetwood Mac. And fell in love with Rob Lowe in Cannonball Run 2. It was also in Karachi where I devoured Nancy Drew mysteries and recited poetry by Blake and Longfellow in Elocution class.

After we moved to America in 1982, Karachi disappeared into the ashbin of memory. I began to think of it more and more as a far and distant land where I once used to live. As for my father, he completely divorced himself from the city that had shaped so many of his attitudes and likings, calling it at one point, “a wild and savage place all gone to seed.”

That’s when I decided to go back. Summer of 2003 was fast approaching and I had nothing better to do after a grueling year of graduate school. I was itching to find out what had become of Karachi and how it had changed. Media reports painted dire scenarios of hired assassins, drug mafias and terrorist havens. Karachi had earned a dubious reputation as a megalopolis of mayhem, the South Asian version of war torn Beirut. It was enough to rob me of all pride associated with my birthplace.

Abboo failed to warm up to my decision. “I don’t know what you’re trying to prove,” he said over the phone. “There’s nothing to see there anymore.”

There was no point in explaining to my father that returning to Karachi would allay the cultural amnesia racked up over two decades during which neither one of us ever went back. Like it or not, we had become strangers to our homeland. But I was haunted by the memories. I had to know, for better or worse, how much of Karachi was still a part of me, and whether or not I would like or hate the place. I needed to glue back all those pieces from the past in order to make sense of the present. It was now or never.

There was no point in explaining to my father that returning to Karachi would allay the cultural amnesia racked up over two decades during which neither one of us ever went back. Like it or not, we had become strangers to our homeland. But I was haunted by the memories. I had to know, for better or worse, how much of Karachi was still a part of me, and whether or not I would like or hate the place. I needed to glue back all those pieces from the past in order to make sense of the present. It was now or never.

The PIA DC-10 makes a smooth landing at Karachi’s Jinnah’s International airport. Passengers in crisp cottons hurry along the gleaming tiled floors reeking of ammonia. I wait for my cousin outside the arrivals terminal where the humidity and salty breezes dig deep into my pores. The Karachi sky reminds me of a moist rag the color of a faded chambray shirt. Just across the parking lot, I see the golden arches of McDonalds. Smart young girls in bootleg cut trousers and strappy heels pass by, appraising me with bold black eyes. I want to tell them that is my country too and I’ve come back to revisit my home, to find out what this place means to me if anything at all.

Natascha Atlas spins with ZZ Top and Pink Floyd, followed by the latest Bollywood and Bhangra. The dance floor pulses with hormones. Girls in halter-tops and tight flared denims shimmy and sway, rake fingers through curtains of jet-black tresses. Blue strobe lights freeze frame their moves, like time-lapse photography. Guys high on Ecstasy cluster in a circle and when they dance, they raise their arms shoulder high, hands weaving elaborate arcs, legs lunging and squatting deep, parodying the stoner’s version of Tai-Chi. Smoke rises from hookahs and joints. Couples smooch. Someone asks for another bottle of Johnny Walker. The host of the party doubles as a bartender. He looks like an early 1980’s version of Rob Lowe with his sea green eyes and chiseled jaw line. His parents are abroad and he has taken the liberty of throwing a little bash at their seaside bungalow. The guests are the hippest and naughtiest people in town.

For the umpteenth time, I readjust my glasses and resist the urge to fold my arms and stroke a troubled chin. The rational part of my brain wants to veer into serious psychoanalysis. Then my emotional side takes over, hammering the heart like a woodpecker gone nuts. Would you get a load of this!

I ask my friend Imran who has accompanied me to the party to pinch my forearm. It hurts. Therefore, this must be real. I cannot be dreaming. Impossible. Highly unfathomable. If this really were a dream, than that gorgeous bartending host would make a bee line in my direction instead of chatting up some girl who would give Jennifer Lopez a major inferiority complex. This is as real as it gets. Never mind the fact that someone is playing Twister with my memory. Imran brings me a vodka tonic despite my repeated requests for mineral water. We soak up the atmosphere melding onto the packed dance floor until the wee hours of the morning.

Produce vendors rolling wooden carts the size of pool tables laden with fruit. Custard apples, pomegranates, papayas. Amroot for guavas. Chicoo ice cream in shades of sand. Buses and minivans racing like maniacs. Men standing on top of car bumpers and truck fenders clinging for dear life. Shalwars and kurtas flapping like untrimmed sails. Peasants riding on top of buses with bundles of smiles. Steam rising from sizzling pavements after a monsoon downpour. Chili peppers wrinkling under the tropical sun. Baby mangoes wrapped in burlap and stowed in tin trunks. Crayola colored laundry flapping in balconies. The heady smell of raat ki raani. Flower sellers hawking fragrant jasmine garlands in the middle of traffic circles. Hot roasted peanuts in newspaper cones.

The images I retain from my childhood in Karachi are bursting with flavor and I long to taste them again. I have brought with me old family photos to spur the wheels of memory. There are camels on the beach and broken sand castles, a milad ceremony at home, commemorating the Prophet’s birthday. I am sitting next to my mother on a white cotton sheet covered with rose petals. Women in gauzy pastel dupattas flutter around us like butterflies. I remember these things happening, but my mind draws a blank when I try to focus on the past. The estrangement is both liberating and unsettling.

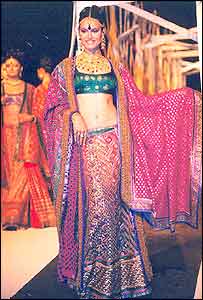

To ward off the initial jitters of homecoming, I spend most of my time flipping through the pages of Pakistani bridal magazines and one lazy Sunday afternoon my aunt and I divide up a stash of thick glossy volumes and ooh and ah over the lenghas in silk and chiffon with sequined tunics and lacy dupattas. Jewelry ads feature earrings and chokers in intricate cuts of diamonds, sapphires, rubies and emeralds. Beaded purses, stiletto heels and evening wraps add a dash of pizzazz. The Pakistani models displaying the elegant wedding attire are downright stunning and sexy. For the next few days, I become addicted to the contents of Libaas magazine and the fall designer collections aired on GEO TV.

One by one, a slew of gaunt faced fashionistas sashay down the runway. They have Muslim names like Vaneeza, Amina, Iraj and Iman. And they are some of the most beautiful faces I have ever seen. It gets all the more alluring with bare backs and midriffs and sumptuous fabrics choreographed to techno beats and the strains of Sting’s Desert Rose. Rehanna Aunty finds my fascination with the catwalk scene a bit too much.

One by one, a slew of gaunt faced fashionistas sashay down the runway. They have Muslim names like Vaneeza, Amina, Iraj and Iman. And they are some of the most beautiful faces I have ever seen. It gets all the more alluring with bare backs and midriffs and sumptuous fabrics choreographed to techno beats and the strains of Sting’s Desert Rose. Rehanna Aunty finds my fascination with the catwalk scene a bit too much.

“It is nothing new,” she says. “Surely you have heard of Freiha Altaf?”

When I profess ignorance, my aunt goes on to tell me about a Pakistani supermodel who rose to world wide fame in the 1980’s, ironically at a time when women’s dress and appearance was under more scrutiny in Pakistan given the stringent Islamization campaign waged by General Zia. Defying the stereotyped image of veiled submission, Frieha Altaf also managed to become a successful business woman who formed her own company known as Catwalk. The first of its kind, Catwalk choreographed and produced fashion shows, music concerts and events. Clients included not just major fashion designers, but global corporate clients such as Motorola, Coca Cola, Kodak and Revlon.

I am beginning to have high hopes for the modeling careers of Vaneeza and company. But then an inadvertent change of channels on the remote submerges me in a whole other world, where the only thing visible is a sea of veils. A female preacher, her face entirely covered in a black niqab or face veil revealing just her pale blue eyes, stands behind a lectern. Dr. Farhat Hashmi, known to her devotees as simply Madam, speaks with a British accent and is apparently quite comfortable with fusing technology with religion, making her interpretation of Islam readily accessible with the aid of Quranic CD’s and PowerPoint slides.

At one of her lectures at a five star hotel, I sit next to a woman in a voluminous ankle length cloak. The rest of her features disappear behind a thick white cloth. Her hair too is swathed in a matching veil. But there is something about her visible hazel eyes that holds me captive. I know these eyes. They remind me of my best friend from school when I was a fifth grade student in Karachi. Surely it cannot be Saira Shah. We had stayed in touch on and off over the years, after I moved to the States, mostly in email. But email is not the same thing as a face to face encounter.

The woman beside me does not look anything like my Saira. I think she is an imposter because this woman who claims to be Saira Shah based on the name I have just seen scribbled inside her notebook, bears no resemblance to the pretty laughing girl whose face I have carried in my mind’s eye for a quarter of a century, a face I imagined would be even more stunning at the age of thirty-five. Maybe she is a stunner. If only I could see her, I would know for sure. But all I can make out are those familiar eyes and her shapeless garments. Surely this cannot be the same dashing Saira, the one who wore silk camisoles underneath her starched white uniforms and vacationed in Paris. I’m afraid she is.

What happened to you?

What happened to Saira is the Al-Huda Institute of Islamic Education. Al-Huda, which translates as guidance, is the brainchild of Dr. Hashmi to propagate Islamic morals and attitudes from a female centric interpretation. I had not heard of the institute before. It certainly did not exist in Karachi when I was growing up there, but it turns out that the Karachi gymkhana, one of the city’s oldest clubs, where my father used to play ping pong and billiards (he called it snookers) has also hosted a religious convention that my aunt sardonically refers to as the FH Phenomenon.

There is an eerie silence as Farhat Hashmi takes to the podium and begins to recite a verse from the Quran in a mellow yet powerful voice. The majority of her audience are society ladies, accustomed to marathon shopping sprees in air conditioned malls and lazy poolside lunches. Posh Anglicized accents now murmur the importance of returning to Islamic values. Critics consider the teachings a blatantly anti-feminist, highly conservative brand of Islam, oddly enough catching on among Pakistani socialites, women who enjoy ample time and money, women who at one point read Shakespeare and Wordsworth like the old Saira, but women who like the new Saira are eschewing their Westernization and voluntarily adopting the mantle of Born Again Muslims.

I wonder why they can’t find a happy medium between both worlds. My progress in deciphering the conundrums of modern day Karachi is going nowhere. It appears downright schizophrenic with these upper crust burqa clad elites, the slinky catwalk babes and those baked and boozy hipsters at the rave. One thing is for sure. There are no crooners left in Karachi. My father was right all along.

* * * * *

Maliha Masood was born in Karachi, Pakistan and grew up in Seattle, WA. She’s the author of the travel memoir, Zaatar Days, Henna Nights: Adventures, Dreams and Destinations across the Middle East (Seal Press, 2007).

Photo credits:

All photos: Author