By Linda Ballou

The blast from the whistle of the locomotive quickened my pulse.

The blast from the whistle of the locomotive quickened my pulse.

“Make way! Make way!.. I’m coming through,” it seemed to say.

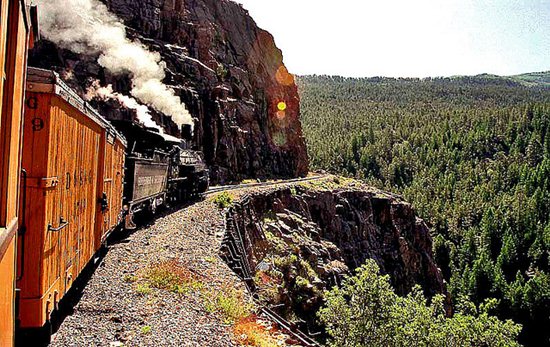

A huge plume of black smoke rose from the stack as the train made its rock-a-billy way along the mountain ledge. I leaned out of the open-air Gondola car to get a better view of the Animus River churning through boulders as big as boxcars. It is one of the few rivers in America that flows unrestricted by dams from headwaters.

A silver-haired woman standing beside me shared my exultation as we snaked along the narrow ravine sheathed in blue-green spruce. She giggled like a schoolgirl as she hung her head in the wind sniffing the crisp breeze, like a happy puppy.

“I think I must have been an engineer in a past life.” I said leaning out of the gondola to face the world head on.

“My parents took me on this trip when I was five,” she said, smiling all over herself. “This is my first time back.”

For over 120 years, this relic of the American West has been chugging up the rugged canyon; a journey of about 45 miles. At eighteen miles an hour the round trip takes all day. The rail was established to haul silver and gold ore from the mines in Silverton to the town of Durango. Despite the formidable terrain, and without the aid of modern equipment, it took hand-laborers only a miraculous nine months to blast through the precipitous stone walls framing the ravine and to erect wooden trestles spanning gaping gullies and the raging river far below.

When the mines were depleted, the train was revamped to accommodate wealthy turn-of-the-century travelers. Today, the lovingly restored train is host to about 1,200 tourists a day in peak season.

When the mines were depleted, the train was revamped to accommodate wealthy turn-of-the-century travelers. Today, the lovingly restored train is host to about 1,200 tourists a day in peak season.

The track through the forest is so narrow you could touch the branches of pine trees that filled the air with their pungent scent. Though only mid-summer, the sage-colored leaves were already tipped orange, crimson and gold. Puffing happily, the train sashayed back and forth across the valley floor through wildflower meadows spiked with stands of columbine and shooting stars, then thundered over wooden trestle bridges high above the reach of the rushing water.

For years, I collected clippings extolling the staggering beauty of this region that includes the jagged Needle Mountains and the vast San Juan forest in the Weminuche Wilderness. It is Colorado’s largest designated wilderness area. My initial interest, however, was generated by the plucky English adventuress, Isabella Bird, who rode solo on horseback through the Rockies in the 1850s. Her vivid descriptions of a landscape which simultaneously thrilled and terrified her left me yearning to see this part of our great country for myself.

The man in my life, a veteran traveler, sated his wanderlust before he met me. What’s more, he does not share the joy I feel when in the great outdoors. So, I chose to venture out of the cozy confines of a comfortable relationship to take this ride alone.

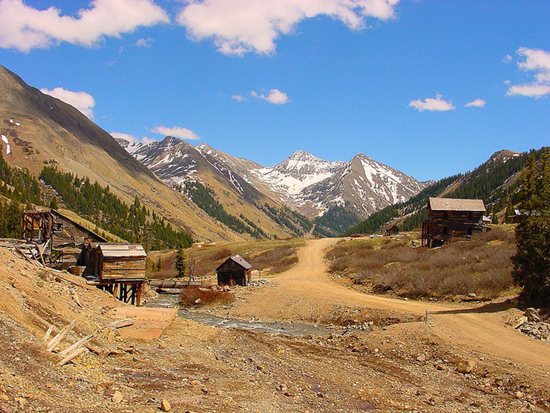

When the train arrived at Silverton, population 500, we were given a few hours to explore the old mining town once famous for its outlaws, ladies of negotiable affections and miners eager to stake their poke on a game of chance. The sleepy Victorian town rests in an alpine valley that is 9,300-feet above sea level and surrounded by 13,000-foot peaks. It is the most active avalanche zone in the country. I looked up to admire the amphitheater of rock spires peering down upon us, sucking in the rarified air as I scoped out the copper colored stream rich with mineral deposits. It is a stroll down Main Street. The summer tourist season is short so shopkeepers in this isolated burg keep prices competitive. I purchased a fire-opal ring from a shop owned by Native Americans for about half of what it would cost in trendy Durango.

When the train arrived at Silverton, population 500, we were given a few hours to explore the old mining town once famous for its outlaws, ladies of negotiable affections and miners eager to stake their poke on a game of chance. The sleepy Victorian town rests in an alpine valley that is 9,300-feet above sea level and surrounded by 13,000-foot peaks. It is the most active avalanche zone in the country. I looked up to admire the amphitheater of rock spires peering down upon us, sucking in the rarified air as I scoped out the copper colored stream rich with mineral deposits. It is a stroll down Main Street. The summer tourist season is short so shopkeepers in this isolated burg keep prices competitive. I purchased a fire-opal ring from a shop owned by Native Americans for about half of what it would cost in trendy Durango.

A blast from the train whistle signaled “All Aboard.”

Once back on the train, I found the still beaming silver-haired lady who told me her name was Sarah. We were both eager to get on with the downhill glide back to Durango. The engineer took pains not to pick up speed as we rattled down the tracks, applying the brakes with a jolt at regular intervals. The effortless descent through the cool glades, across the rushing Animus seemed a fitting reward for the massive coal-fired locomotive that had huffed and puffed its way 3,000-feet up the mountain. This time we rocked through the forest without the billow of dark smoke rising from the engine to mar the crystalline air.

All the way down though the gorge, Sarah mirrored my awe over the ever- shifting patterns of mother-nature’s handiwork. “It’s more vibrant than I remembered.” She said, blinking back tears. She told me that since her trip as a child through this canyon her eyesight had grown progressively worse, until at sixty-four she was nearly blind. Six months ago she had undergone laser surgery and this trip was to celebrate the success of her operation. All of her life she held onto the visual memory of the ride up this canyon in her slowly darkening world, and today she was seeing it again with “new eyes.”

The joy of sharing the day with someone who appreciated the undisturbed beauty before us fully as much as I did, meant more than any souvenir I could buy. I was thrilled to discover another “haploid”, someone like myself, totally engaged in the state of exploration, in “just seeing.”

The joy of sharing the day with someone who appreciated the undisturbed beauty before us fully as much as I did, meant more than any souvenir I could buy. I was thrilled to discover another “haploid”, someone like myself, totally engaged in the state of exploration, in “just seeing.”

Marcel Proust once said, “The real voyage is not traveling to distant lands, but in seeing the world with new eyes.” It was fitting that on this fledgling venture at traveling solo I felt I too was also seeing the world with fresh perspective. The rush of the spinning aspen leaves glinting in the sun, the sight of a stag swinging his antlered head from side to side watching us pass through his green world and the beauty of languid butterflies drifting on the breeze remain stored in a quiet place in my heart.

Since that trip, I made it my mission to get to as many pristine places as I can before they are no more. As for the man I leave behind, on those exploits that hold no appeal for him, he is proud and pleased that I’ve made my own way to where I needed to go. He is always glad, and maybe a little bit relieved to see me return, and I’m always glad to be home.

*****

Linda Ballou’s mission is to get to as many naturally beautiful places as she can before they are no more! She has hiked, biked, kayaked and ridden on horseback through some of our most precious wilderness areas. Her soon-to-be published collection of travels essays, Lost Angel Walkabout, speaks of the healing power of the wild.

*****

Photo credits:

Durango and Silverton Train: Don O’Brien

Silverton Old Mining Camp: Gloria Manna

Silverton Town: joevare

Silverton Colorado: Elaine