by Maliha Masood

The jeep scaled up and down dunes, skidding in wide turns and crunching its tires on the squishy sand. I felt like a rubber ball bouncing inside a vacuum.

The jeep scaled up and down dunes, skidding in wide turns and crunching its tires on the squishy sand. I felt like a rubber ball bouncing inside a vacuum.

We spent our first night near Acrobat Mountain, setting up camp in an alcove of beige boulders with arched formations that reminded me of Utah. Badri lit a fire and roasted chicken on skewers made out of twigs for our first dinner together. Afterward, he brewed sweet mint tea and plied me with dozens of tiny glasses of what he called “Bedouin whiskey.” The rich, lilting voice of the Egyptian diva Um Khoulsoum flooded the still desert night from Badri’s cassette player. We listened to the classic song Inta Omri, which means you are my life, countless times. Badri translated some of the lyrics from Arabic to English.

“The best concert hall in the world!” He waved his hand at the surrounding expanse of stubby rocks and ridges of powdery dunes. It was impossible to believe that we were less than two hundred kilometers away from Cairo. My ears stretched into the cool night air and listened to the desert’s silence.

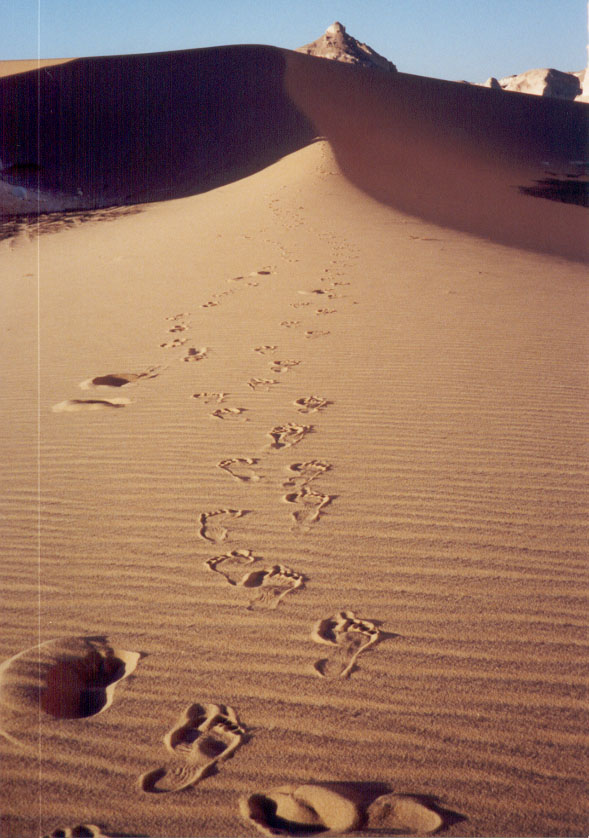

It was incredibly loud, so loud that I could hardly bear the sound. And it was heavy, it filled my soul with a certain weight I could not place. When I mentioned my concern to Badri, he nodded and told me that this silence was so distressing to one European woman in a previous trek that she had to quit her journey prematurely. I wondered what it was she couldn’t handle.In the early morning, Badri was still slumbering on his thin mattress next to last night’s fire. I grabbed my water bottle, some mouthwash and wet wipes and went in search of a bathroom. Away from the camp, the land began to curve upward in a series of frozen waves. I climbed a dune, fascinated by the sight of my footprints etched in the slithery grains. Reaching the crest, I looked out into a featureless space of sand and sky.

On day two, we headed toward the Libyan border, entering the cusp of the Western Desert that branches out into the Sahara. An immense wilderness unfolded and held me captive. We discovered a plain with no visible limits. Only our jeep tracks indicated any signs of life, carving deep incisions in the chocolate brown sand. This time Badri found a fabulous campsite. We scaled the ridge of a long dune and inched down into a hollow depression flanked by boulders as if they were curtains.

It was still mid afternoon. After we set up camp, I went exploring and felt as if I was getting drunk on light and space, the headiness of just being able to breathe, just being alive. I started playing a little game, walking backward in the sand just to watch my feet leave their imprints. As I kept moving, I sensed my borders shrinking, getting smaller and smaller until my mind dissolved all its rationales, theories, prejudices, and fears, leaving behind an emptiness, which was not a void, but a type of wholeness I had never experienced before.

Later in the evening after dinner, Badri and I took a long walk together, barefoot in the cold sand. His shadow roved next to mine and we walked without talking much. I only asked him how he managed never to get lost in that vastness.

“Learn to read the stars, the language of the sky,” he said.

I threw my head back at the black dome sown with tiny silver sequins that appeared permanent and ageless. As I continued staring at the stars, I began to see my journey as a process rather than a destination. The prattling need for structure to give it a necessary weight faded into oblivion, replaced by a more sure-fire desire to trust in the unknown, to travel as a nomad whose only compass is intuition. A line from the Quran chimed in my head. Everywhere you turn is the face of God.

That night, I slept on top of a cold sand dune. There was no trace of any other human being. Not even the slightest wind, just a great stillness as if time itself was suspended. I was totally exposed and vulnerable to the infinite space around me. A space without walls, furniture, or restrictions, a space studded with hundreds of self-reflecting mirrors, with nowhere to run or hide from myself. Everywhere I looked, there was only me. The sound of my breathing and the soft thuds of my beating heart compelled me to fully absorb my solitude and revel in it.

After watching the sunrise, I ran down to the camp to wake up Badri. He had already started packing and was ready to head back into civilization. By late afternoon, we were suddenly pulling into the main drag of Bahariyya. Badri shook my hand and put me on the last bus to Cairo. I sat in the back row and waved at the desert fox until he shrunk into a black pinpoint. Only the sand granules in my shoes reminded me that it was not just a dream.

*****

Maliha Masood was born in Karachi, Pakistan and grew up in Seattle, WA. She’s the author of the travel memoir, Zaatar Days, Henna Nights: Adventures, Dreams and Destinations across the Middle East (Seal Press, 2007). Visit her website here.

Photo credits:

All photos: Author