by Shae Healey

Food and Drink Category winner – WanderWomen Write Contest 2010

It’s 5 a.m. and I’m wide awake studying the sharp slant of the ceiling and listening to the guttural purr of a stray cat in heat. The sharp moan of distress and yearning cuts through the winding alleyways of the medina and collides with the faint crackle of a nearby loudspeaker.

It’s 5 a.m. and I’m wide awake studying the sharp slant of the ceiling and listening to the guttural purr of a stray cat in heat. The sharp moan of distress and yearning cuts through the winding alleyways of the medina and collides with the faint crackle of a nearby loudspeaker.

A sound like the acoustic version of stiff bedsheets shuffling fills the air and ignites into the impassioned cry of call to prayer. After a few days in Istanbul and Marakesh, the wail of mosque music has become just another street sound, blending into the mix of revving motorcycles and the pushy shouts of shopkeepers. But this call, this morning, is refusing to compromise. This call is ripping through locked doors and slipping beneath windowpanes, arriving at every bedside with unmistakable clarity. This call is replacing every dream with the image of a man in rapture, eyes squeezed tight, arms outstretched, voice rushing from a body with the force of pure divinity.

This call makes me certain that I am but one of millions lying awake in silent awe of Islam in pious heat. This call marks the beginning of Eid al-Adha, an important religious holiday celebrated by Muslims worldwide to commemorate the willingness of Abraham to sacrifice his son as an act of obedience to God. Thanks to the good grace of the new moon, I’m here to witness Fez celebrate, one sheep at a time.

It’s 5:15 a.m. and the call to prayer has finished. As a non-Muslim, reverence quickly gives way to humor. I pull back the covers, place my feet on the cold tile and mumble something about a call to “pee.” On my way to the bathroom, I notice that my girlfriend, Whitney, is alert enough to recognize blasphemy. She rolls to the side of the bed and smiles, curls her body in prayer pose and faces east in reparation.

the side of the bed and smiles, curls her body in prayer pose and faces east in reparation.

It’s 8 a.m., and I’m walking in disbelief down the empty artery of Fez’s main drag where, on any other day, locals and tourists pump through the street as if fueling the heart of the city via critical mass. Today Talaa Kebira looks more like tumbleweed territory with hundreds of shop gates pulled tight against the cobblestone.

My mom, Whitney and I walk shoulder to shoulder, breaking the single-file strategy we adopted with Darwinian urgency during our first day in Morocco. There are no donkeys; there are no food carts; and, aside from the occasional man, grinning and running with multiple knives in hand, there are no people. A few meters down the road, we pass a straggler pushing a cart with a sheep on board. We’re not from around here, but we know enough to recognize that, in  a non-Muslim neighborhood, this would be the poor sucker stringing his holiday lights on Christmas morning. But, like any other man in a gandora today, this fellow is teeming with joy. He notices us, stops, and widens his eyes. Like an eager school boy answering a rhetorical question, he raises his voice, and draws an imaginary line across his throat with his thumb. “Sheeps!” he blurts.

a non-Muslim neighborhood, this would be the poor sucker stringing his holiday lights on Christmas morning. But, like any other man in a gandora today, this fellow is teeming with joy. He notices us, stops, and widens his eyes. Like an eager school boy answering a rhetorical question, he raises his voice, and draws an imaginary line across his throat with his thumb. “Sheeps!” he blurts.

Yes, today is the day of the sheeps! This word — with the excited tone and the sharp pronunciation, the abrupt hand gesture and the poor grammar — has become something of a greeting between tourists and locals during the days preceding Eid al-Adha. I’ll admit it: I even said it to myself while pulling on my pants this morning. It’s catchier than a pop song on repeat.

“Yes, Happy Eid!” we reply in unison, and the baa of the sheep is lost beneath hurried footsteps, leaving my mom, Whitney, and I with only time to kill before tuning into the local TV station at 9 a.m. According to our landlord, the king is in town to kick off the big day with a televised throat slitting that is meant to open the blood gates for the rest of the city.

It’s 8:30 a.m., and I hear it before I see it: a waterfall… a waterfall in the city… a waterfall of blood gushing from the city wall. Eight feet to my left and fifteen feet above, there is blood projectile-vomiting from a fist-sized hole overhead. There are mixed chunks of unidentified origin pounding down like hail, staining the concrete wall before making a grand finale in a foamy crimson pool in the street’s gutter. Had I not known about the sheeps! I might have gone into shock. But I know about the sheeps!, so I am not paralyzed by fear. I am laughing out loud because someone  doesn’t need the king to celebrate.

doesn’t need the king to celebrate.

It’s 9:05 a.m., and there’s still no king on the TV. The three of us are sitting in a cafe full of Moroccan men. We are white and we are women. The only other white woman in the restaurant is Katy Perry who is quite literally crawling across the TV screen, and I notice that I’m blushing. There is a loud clatter of hooves followed by a dozen men on horseback with blood-stained shirts. They are shouting and singing their way through the streets. A police officer arrives and begins to joke with the men in the cafe. He is waving a foot-long knife like a baton conducting the laughter of the group seated before him. A shuffle ensues, and one man is pushed forward and tucked under the police officer’s arm. The knife is drawn, and all parties are smiling like their lives depend on it. Thank goodness we are not sheeps!

It’s 9:30 a.m. and we are walking back to the riad. According to Moroccans, a riad is a traditional house with an interior garden or courtyard. According to ex-pats, a riad is a sure-fire financial investment with a marketable location.

A strange phenomenon is occurring in Morocco, and riads are at the center of it. Thanks to the steady stream of tourism, low-to-middle-class Moroccans can sell their homes to foreigners in exchange for a bigger house in a more affluent neighborhood. In short, Moroccans are getting the hell out of dodge so that tourists can vacation there. The swap seems to work out nicely for all parties. Our Australian landlord, however, needs to brush up on his facts. The king, as it turns out, is not in Fez this morning. Although one of the king’s wives is from Fez, he is choosing to celebrate Eid al-Adha in Rabat where he will be televised at 12 p.m. not 9 a.m. Purchase a riad! [Cultural knowledge not included].

A strange phenomenon is occurring in Morocco, and riads are at the center of it. Thanks to the steady stream of tourism, low-to-middle-class Moroccans can sell their homes to foreigners in exchange for a bigger house in a more affluent neighborhood. In short, Moroccans are getting the hell out of dodge so that tourists can vacation there. The swap seems to work out nicely for all parties. Our Australian landlord, however, needs to brush up on his facts. The king, as it turns out, is not in Fez this morning. Although one of the king’s wives is from Fez, he is choosing to celebrate Eid al-Adha in Rabat where he will be televised at 12 p.m. not 9 a.m. Purchase a riad! [Cultural knowledge not included].

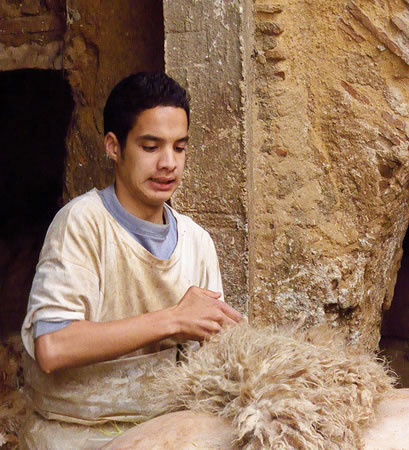

It’s 9:45 a.m. and lambs are roasting on an open fire. King or no king, Talaa Kebira is peppered with fire and smoke where coal and wood burn beneath mattress frames. These makeshift grills are used to cook various sections of dismembered sheep — most notably, the head and the legs. The chefs appear to be teenage boys. Some are laughing and some are what the pun-minded might describe as deathly serious. Mood aside, these boys have a routine, and because they fit the age-range of the young people I used to work with, my mind regresses to office mode and spits out a job description:

The Street-side Chef is responsible for all or part of the following duties:

– Poking sheep heads with a stick

– Rotating sheep legs until blackened;

– Securing heads and/or legs between foot and ground;

– Scraping charcoal from bone with sharp knife

– Removing horns from head

– Repeating the above tasks until all buckets are empty

My eyes begin to water, and I question whether or not I have the qualifications. The fire burns on, and we climb the stairs up to our riad for an aerial view.

It’s 10:30 a.m. and I’m looking out on a smoky skyline of minarets, satellite dishes and antennas. Stray cats and laundry lines connect the hundreds of terraces that form Fez’s crowded medina. Eid al-Adha is in full swing, and depending on where I look, sheeps! are alive and tethered, dead and skinned, or squirming in some sort of unpleasant purgatory. The rooftops are bustling with action which makes spectating strangely easy. Religious traditions are exposed as if the ceilings were torn off for viewing pleasure. For a religion built on veiled privacy, I feel privileged to witness the openness of today’s sacrifice. Allah may be looking in, but so are we, and everyone seems to appreciate the extra eyes.

It’s 12 p.m. and the family across the alley seems to be one of the few to wait for the king’s call. A black cat prowls above the scene, and birds are flying in mechanical circles, overwhelmed by the endless possibilities of fresh meat. The laundry is hanging limp on the clothesline waiting to dry, and the sheep is tethered by a green rope waiting for slaughter. Two little girls chase each other on top of checkered tiles the color of dirt. The little girl waves at us because, in her world, we are more of a surprise than the fate of the sheep. For a moment, there are three women on each side of the alley, creating a sense of symmetry in the midst of great contrast. My mom, Whitney, and I continue watching as a young boy and two men step onto the scene.

It’s 12:20 p.m. and the sheep has just been flipped on its back. A small wall obstructs our view, but we can see one of the men mouthing a prayer, and we know that the knife is drawn. Blood flows silently onto the terrace, and the grandmother begins to sweep.

The sheep kicks and lets out a gargled baa, and the men shake their head at what should have been a faster kill. Two snaps of legs breaking, and the sheep is tied by its feet. The children are jumping rope, and the men are skinning the carcass. The skinning process reminds me of pulling off pants that are two sizes too tight in the dressing room. It’s easier to think of it that way at least. Once the skin has been removed, the sheep is slit down the middle, and the intestines and internal organs are removed. The stomach lining is hung to dry which does not seem all that unusual given its resemblance to a torn rag. The sheep is untied and placed in the arms of one of the men. The shape of the animal is still intact, and its held in a way that makes the sheep look tired after a long day. I can’t blame it. The twisting of my stomach is calmed by the intentionality and appreciation with which the man carries the carcass. He is purposeful, he is thankful, and he is proud.

It’s 2 p.m. and we’ve been wandering the streets for an hour looking for food. Trucks and carts are filled with sheep skins, and we are careful to step over the occasional pile of intestines and discarded bloody clothes. After much searching, we succumb to the fact that McDonalds is the only restaurant open today. I make a meal out of french fries and ice cream, and I think about all of the death and all of the life that I just watched. The sun is not close to setting, but I’m exhausted after witnessing and processing the existence of yet another world that is so entirely different than my own.

It is 2:05 p.m. and I am speechless.

Photo credits:

Sheepskin: }{enry

Bedroom in Riad: }{enry

Rooftops in Fex: }{enry

Eid al-Adha scene: Brian Hillegas

Riad courtyard: Laura and Fulvio’s photos