by Sharon L. Morris

Lurching up the hill toward Jaipur’s Amber Fort on a brightly painted elephant, I saw my grandchildren grinning back at me from the elephant just ahead. Relaxing my grip on the flimsy wooden platform, I remembered how often we’d enjoyed reading books about Babar the elephant. At that moment, spending August in steamy India didn’t seem like such a crazy idea after all.

Lurching up the hill toward Jaipur’s Amber Fort on a brightly painted elephant, I saw my grandchildren grinning back at me from the elephant just ahead. Relaxing my grip on the flimsy wooden platform, I remembered how often we’d enjoyed reading books about Babar the elephant. At that moment, spending August in steamy India didn’t seem like such a crazy idea after all.

We had our doubts when planning the trip. Traveling in India can be difficult for adults, much less children. We were a group of grandparents, parents, children and friends ranging in age between 7 and 70. How would everyone cope with the heat, the clothing constraints (no tank tops or shorts), the very different culture and the spicy food? Could we even afford to go on such an adventure half way round the world?

To our relief, the children handled the challenges as well as the adults, sometimes even better, as we traveled from Delhi to Agra, then on to Jaipur and other cities in Rajasthan. We chartered buses, rode trains and hired cars and drivers. We stayed in comfortable hotels where the adults could sip a gin and tonic while the children splashed in the pool after a hot day of sightseeing.

And the cost? Traveling in a style we could never afford at home, a family of four paid $1,000 for a car and driver, eight nights at hotels with breakfast, and a round-trip train ticket to Agra. In comparison, the same family would pay $1,000 for two nights in Anaheim and tickets to Disneyland for three days. Even factoring about $1,300 for airfare from Seattle, we decided the adventure was within our budget.

And what an adventure it was. Our trip began in Delhi, where we recovered from jet lag and eased into Indian customs and food. We discovered the children liked tandoori dishes or those based on rice, like biryani and pulao. They were soon sipping fresh lime sodas and scooping up their food with a chapatti or even their fingers. We also found restaurants that served familiar food, like pizza.

We visited the Red Fort, the seat of Mughal power when the city was the capital of Islamic India. As we came to expect, getting there was half the fun. After taking a subway to Connaught Place, we hailed bicycle rickshaws. Our small, wiry drivers peddled us through the monsoon-soaked streets, dodging pedestrians, cars, pushcarts and the ubiquitous sacred cows. A young boy scurried alongside us doing back flips in hopes of a tip.

We pulled up to the Red Fort, a sandstone structure more like a sumptuous castle than the wooden forts in old cowboy movies. Inside the massive walls Emperor Shah Jahan had built a white marble palace, government buildings and a mosque. We could imagine him sitting on the gold Peacock Throne or relaxing in a bath filled with rosewater.

After Delhi, we headed for Agra, site of the Agra Fort and the Taj Mahal. The trip down was a good time to read about the city’s history, which contains enough romance, treachery and violence to rival action-packed video games. Akbar, who built the fort, was considered the greatest of the Mughal rulers, expanding his empire to cover most of northern India.

Our 13-year-olds were amazed that Akbar became emperor when he was their age. Known for religious tolerance, Akbar included Christians and Hindus as well as Muslims among his many wives. Nonetheless, Akbar sometimes behaved like other Mughal emperors. To celebrate a military victory he once built a tower from the heads of dead Hindu soldiers.

wives. Nonetheless, Akbar sometimes behaved like other Mughal emperors. To celebrate a military victory he once built a tower from the heads of dead Hindu soldiers.

It was Akbar’s grandson, Shah Jahan, who built the Taj Mahal. No picture prepared us for the impact of that stunning building. Even our blasé boys admired the exquisitely carved marble with gemstone inlays. The girls loved the story of how a heartbroken Shah Jahan built the mausoleum as a tribute to his wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died after the birth of their 14th child.

“The embodiment of all things pure,” is how Rudyard Kipling saw the Taj Mahal. “Wildly extravagant,” is how Aurangzeb, Shah Jahan’s third son, might have characterized it. Determined to become emperor and return the country to strict Islamic rule and fiscal responsibility, Aurangzeb killed his brothers and imprisoned his father in the Agra Fort. For the last eight years of his life, Shah Jahan had to gaze at the Taj Mahal from inside a tower across the river.

Our next stop was Jaipur in Rajasthan, the land of the swashbuckling Rajputs and their maharajas. The Rajputs were such fierce warriors that even the Mughals found it hard to subdue them. When they weren’t fighting, the maharajas knew how to live a fine life in water-cooled palaces, with candlelight reflected in hundreds of tiny mirrors in the ceiling.

As we drove through the countryside, our driver had to maneuver around herds of sheep and goats along with the usual free-ranging cows. We passed knobby-kneed camels pulling two-wheeled carts, the drivers sitting high atop a pile of bulging burlap bags. Even the camels were decorated, their haughty demeanor enhanced by beaded necklaces.

Quite different from the ferocious Mughals and fighting Rajputs are the peaceful Jains we met in Ranakpur. They believe in non-violence to every living thing, some covering their mouth to avoid harming insects that might be inhaled. As we entered the Adinath Temple in Ranakpur, we had to remove all animal products, including leather belts and wallets. Inside we were guided by a saffron-robed monk, who showed us 1,440 intricately carved marble pillars, no two alike.

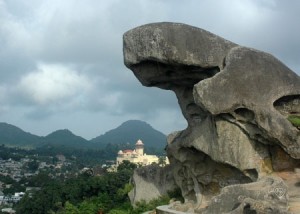

On the way to nearby Mt. Abu, a hill station at the end of a steep, winding road, monkeys joined our outdoor menagerie, walking along the road, some with babies clinging to their bellies. When we got out of the car, the bolder monkeys moved in, ready to grab any food we might have. Nearing the top of the hill we glimpsed our hotel, the elegant Jaipur House, formerly a maharaja’s summer home.

In the end, it wasn’t staying in that imposing house we’ll remember about Mt. Abu. It was the connection we made with family on top of Toad Rock, a natural stone formation that looked like a toad about to hop into Nakki Lake far below. Nestled into an alcove in the rock was a refreshment stand, where the parents sold bottled water, soft drinks, tea and fresh fruit. Their four children looked at us curiously.

As we caught our breath from the climb, the little girl walked over to our Israeli granddaughter, and said in soft, but excellent English: “What’s your name? Mine is Narayni. How old are you?”

“My name is Yael and I’m seven,” she answered.

“I’m seven too,” said Narayni as she reached out her hand. “Will you be my friend?”

The pictures we took that day show the two  girls, one in green Crocs and the other barefoot, holding hands and smiling. They spoke to each other in English, a language both were learning in school. With the help of Narayni’s older brother, the girls exchanged addresses and promised to write.

girls, one in green Crocs and the other barefoot, holding hands and smiling. They spoke to each other in English, a language both were learning in school. With the help of Narayni’s older brother, the girls exchanged addresses and promised to write.

Back home again, the children couldn’t stop talking about their trip to India. They mentioned the elephant ride, the camel carts, the mischievous monkeys, and the brilliant colors everywhere. They could speak with some authority about teenage emperors and magnificent forts. And everyone who climbed Toad Rock that day remembered the two little girls who wanted to be friends.

* * * * *

Since retiring from a 33-year career in public health, Sharon Morris has enjoyed sharing her travel adventures through writing and photography. Sharon has kayaked in remote locations for 25 years and traveled extensively in SE Asia, India and the Middle East. She currently enjoys sharing her passion for travel with her grandchildren, who’ve trekked with her in India and kayaked alongside her in Alaska. Sharon has been published in Kayak Touring, Adventures NW, Old Times and The Seattle Times.

Photo credits:

Camel: The Dilly Lama

Monkey at Red Fort: youngrobv

All other photos: Author