by Erin Byrne

We need in love to practice only this: letting each other go.

We need in love to practice only this: letting each other go.

For holding on comes easy — we do not need to learn it. — Rainer Maria Rilke

Little by little, one travels far. — J.R.R. Tolkien

When you take your child out into the world, there is a risk that forces will be unleashed that coast them beyond your reach: forces of history, mankind, the world; forces inside them. When your child experiences a place, or grasps a piece of history that gives him a fuller sense of reality, he drifts in directions you could never foresee… on his own.

When my son Brendan was eleven years old, inside the creepily cold dungeon of Warwick castle in England, he heard the details of how The Rack worked on the human body. Feet fastened to one roller, wrists chained to the other, and after a few cranks, cartilage, ligaments and bones snapped and popped, limbs permanently separated from body. The real Rack inspired in Brendan kinder treatment of his friends and his brother — he still gave them the occasional smack, but he never again yanked their arms or legs in that horrifying way boys do. He was also much gentler with his dog.

Brendan visited the hallowed ground of Saint Andrew’s Golf Course in Scotland and acquired a meticulous observation of the rules and courtesies of the game. After that trip, anyone who dragged his clubs across the green faced his wrath. He fly-fished on the River Nore in the land of his Irish ancestors. When he got home he looked in the mirror with a new admiration for his own fair skin and reddish-blond hair, and dedicated himself to perfecting his inborn flair for fly-casting. He flew the Irish flag proudly. Next, he developed a new sense of savoir-faire in Paris, which he used with much success on cute girls at summer camp.

Pointe du Hoc, a desolate plain high above the northern coast of France, with its grand story of sacrifice, took my sixteen-year-old son further than any of his previous travels. Before his plunge down into one of the bunkers there, Brendan had soaked up what life had to offer with little thought of what he would give back to the world.  After this trip, he changed in a deeper way. He pulled his truck over to the side of the road whenever he saw anyone standing helpless, volunteered to work with middle school kids and made plans to become a firefighter in nearby mountains.

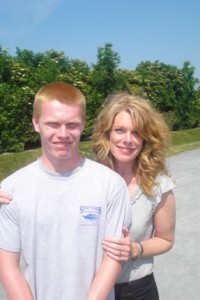

Brendan and his best friend Corbin, two handsome, hot-blooded, flag flyin’ Americans, had prepared for this trip to Paris and Normandy. For years, Corbin’s grandfather had told stories of his landing at Utah Beach. Brendan aced U.S. History his sophomore year, immersing himself in the story of D-Day. I decided to follow these two and observe–a new, more detached role for me.

The week before going to Normandy, we visited the Invalides Musée de l’Armée’s World War II Rooms in Paris. Their teen spirits remained lighthearted at first as they meandered through the displays of uniforms, scoured the strategic maps and stared at the photos of Hitler swinging his arms under the Arc de Triomphe. They posed pointing toward the camera next to the Uncle Sam poster and pretended to fire weapons; the sound “ch-ch-ch-ch” automatically flew out of their mouths, evoking boyhood war games conducted high up in a tree.

These two comrades had fought many an imaginary war side-by-side. When they were little kids in our woodsy backyard, their main headquarters had been their earnestly constructed tree fort. Getting up was the biggest challenge, the most fun for pretending: hoisting, heave-ho-ing, hollering and hangin’ on by their fingertips.

“Hurry, hurry!” they would shout, looking over their bony little shoulders at pretend soldiers falling into the chasm below. They’d toss down ropes, under heavy fire from snipers the whole time. Once up, they’d be trapped up there for boy-hours (weeks, years, decades). Reinforcements always came; they were rescued just in time. They were the good guys, and the enemy was a murky, faceless threat. Sweet is war to those who have never experienced it, as the Latin proverb says.

the chasm below. They’d toss down ropes, under heavy fire from snipers the whole time. Once up, they’d be trapped up there for boy-hours (weeks, years, decades). Reinforcements always came; they were rescued just in time. They were the good guys, and the enemy was a murky, faceless threat. Sweet is war to those who have never experienced it, as the Latin proverb says.

Once, I climbed up for a safety check of that tree fort: rusty nails, huge spiders, loose boards, and an exposed edge high enough for an arm-breaking fall. I climbed right back down, forcing the dangers from my mind. Some risks are better left unconsidered; that fort was no place for a mom. Instead I watched from the kitchen window as I moved the emergency rations from the cookie sheet to foil.

After their moment of nostalgia for the tree fort wars, Brendan and Corbin sauntered through Musée de l’Armée. When one would slow down and begin to thoughtfully ponder some display, the other would poke him in the ribs, and the mood would bounce back up like a cork in the water. Such is the buoyancy of teenage boys.

In a dark alcove of the museum, silent scenes projected upon the wall — the Normandy landings flickered jerkily in black and white. Boats in shaky shades of gray spilled over with boys not much older than Brendan and Corbin, their bodies tense and alert, eyes scanning the beach. Soldiers staggered, crawled and clawed through wet sand; some collapsed, twitching, after only a few steps. A few ran across the chaos and began climbing directly up the side of a cliff. A steady stream of images flashed: soldiers running up on dry land, barbed wire, guns, camouflage. Underneath helmets, faces of naked fear.

Brendan and Corbin forgot their demeanor and sat fixated, their mouths closed tight. I stood apart feeling distant. I looked at them sitting speechless on the bench, and had an image of one hoisting the other up into the tree fort just in the nick of time. The black and white images of real boys doing this on the Normandy beach gave me a stab of protective fear and dread at the prospect of taking Brendan and Corbin to the place where it had all happened; I knew it would stun them.

Two days later, on our way to the beaches, they nudged each other in the back seat, traded iPods, bent their heads together viewing the many photos they’d taken of themselves, and guffawed at each other’s jokes. Every once in a while Brendan said in a solemn voice, “We’d all be speaking German now if it wasn’t for our American boys.” The next moment he gibberished in German and the mood popped back up. Corbin  alluded, with a furrowed brow, to his grandfather’s tales of heroism in the face of danger, but a second later doubled his chin comically and imitated his grandpa.

alluded, with a furrowed brow, to his grandfather’s tales of heroism in the face of danger, but a second later doubled his chin comically and imitated his grandpa.

Brendan arrived at Pointe du Hoc unknowingly ready for the history of the place to move him. He’d been in the same state at five years old when I’d given one last push on the edge of his bike seat and he pedaled ahead on the grass. When I let go, he coasted with ease and it was I who felt wobbly. But then I looked, and felt I was really seeing him: a skinny five-year-old in a baggy black t-shirt and jeans, his helmet catching the sun, glided away towards independence.

Pointe du Hoc is high above Omaha and Utah beaches. Back in 1944, the mission for the U.S. 2nd Ranger Battalion was to land by sea at the foot of the cliffs, scale the 40 meter high vertical face using ropes, ladders, and grapples under enemy fire, then surprise the Germans at the top of the cliff in order to capture the battery and wipe out the big guns at Pointe du Hoc.

The Rangers arrived forty minutes late because of an off-target landing.

As they climbed up, the Germans (who had already moved the weapons) had time to recover from heavy air bombardments, climb out of their dugouts, and man their positions. The Rangers began to climb, but the ropes were soggy and heavy and only one rocket sent up top containing the ladders made it. The Germans started cutting the ropes. They rolled hand grenades off the cliff edge. They leaned over and fired down on the Americans.

Once up, movement meant crawling. Private Robert Fruling said he spent two and a half days at Pointe du Hoc, all of it crawling on his stomach. He returned on the twenty-fifth anniversary of D-Day, “to see what the place looked like standing up.”

Back in the day, Brendan and Corbin had spent much of their time crawling into the ‘stickly fort’. The best thing about the hideout carved out of the blackberry bushes was its ability to keep out the enemy and/or parents. I knew better than to try to squeeze into the four-by-four foot warren. I acted as the medic-on-call in emergencies only, for often blood was shed getting in and out on hands and knees, branches with sharp thorns smacking at little boy bodies. Yes, they had hunkered down in many a foxhole right in their own backyard, and their bodies still had the scars to prove it. But this was the real thing.

On the Normandy plain that day, headquarters were hastily set up on a concrete battery overlooking the  beach below where wave upon wave of men were essentially being massacred.

beach below where wave upon wave of men were essentially being massacred.

Sargaent Frank South, a nineteen-year-old medic, remembered, “The wounded [were] coming in at a rapid rate, we could only keep them on litters stacked up pretty closely. It was just an endless, endless process. Periodically I would go out and bring in a wounded man from the field, leading one back and ducking through the various shell craters. At one time, I went out to get someone and was carrying him back on my shoulders when he was hit by several other bullets and killed.”

Under machine gun fire from all sides, with dwindling ammunition and no rations, the 2nd Battalion waited for reinforcements: Company A of the 116th Regiment.

Company A of the 116th Regiment had been wiped out at the beach.

The Rangers lost 135 men out of 225. The remaining 90 ventured inland, then found and destroyed the well-camouflaged guns, ready to fire in the direction of Utah beach, with piles of ammunition around them and Germans in an open field 100 meters off. After accomplishing their mission, they courageously held out two days longer, hiding in the bunkers.

When we arrived at Pointe du Hoc, Brendan and Corbin stood still for a moment on the concrete battery looking over the beaches. Brendan’s eyes squinted and his mouth clamped shut, pushing his profile up into a grimace. I was snapping photos, and through the camera lens it looked to me like suddenly he heard every sniper’s footsteps, saw in his mind’s eye the bullets puncturing the skin of falling soldiers. He looked like he felt every particle of fear that had been there on June 6, 1944.

I remembered the green plastic army guys I used to find scattered around our house, 1 ½ inches high, halted in a variety of poses: leaning on high alert, firing a gun, hand by the mouth hollering to comrades, crouching, crawling on their stiff green stomachs. I would find them after they had climbed the cliff (wall), sometimes hanging from ropes (shoelaces) and finally reached the battlefield (windowsill). Up on this  Normandy plain I imagined I saw them come alive, crawling, crouching, shouting, firing. And when one of them ran past me, the face underneath the helmet had narrowed eyes and chiseled cheekbones.

Normandy plain I imagined I saw them come alive, crawling, crouching, shouting, firing. And when one of them ran past me, the face underneath the helmet had narrowed eyes and chiseled cheekbones.

I imagined the 135 mothers of the boys who had died there sixty-five years ago. I wondered if, when they received word of their sons’ deaths, their minds had flashed back to the days when their boys had played at war. I wondered if there had been one who had known, even before she was officially informed, that her son had coasted away from her forever. I wondered if any of those mothers had come here afterward and staggered around on the grassy knolls or ventured down into the gray concrete bunkers.

Pointe du Hoc has been left undisturbed, except for fencing and footpaths, which Corbin and Brendan naturally did not keep to. They ran up and down the craters created by bombs and shells, past blast marks of grenades and bullet-scarred chunks of concrete, but it was when they stepped down into the hideout that they sobered.

They lumbered down a path buried in overgrown grass, ducked their six-foot high frames under the low entrance and clamored down into the bunker. I followed. The three of us stood in a patch of sunlight, our eyes adjusting to the dimness of the gray rectangle.

Down in the cramped dimness sixty-five years and nineteen days after D-Day, the air was still  and eerily silent, as if the spirits of the American boys who fought there still remained. “That’s the hole where the gun pointed out,” Brendan murmured, as the light shone in from above without warmth. “What’s that on the wall–is that blood?” Corbin whispered. “They must have…” speech deserted him. There was indeed a rust-colored stain on the wall. I suddenly felt this was not the place for me, so I climbed up and out.

and eerily silent, as if the spirits of the American boys who fought there still remained. “That’s the hole where the gun pointed out,” Brendan murmured, as the light shone in from above without warmth. “What’s that on the wall–is that blood?” Corbin whispered. “They must have…” speech deserted him. There was indeed a rust-colored stain on the wall. I suddenly felt this was not the place for me, so I climbed up and out.

It seemed Brendan had spent his boyhood preparing for this moment, far from his own backyard, years away from a time when his mind had first played with the notions of war, sacrifice, or the possibility of his own death. Inside the concrete rectangle as real history crashed into childhood imaginings, this moment marked a shift in his very self.

As Brendan ducked under the low entrance and emerged, blinking, from the underground bunker, I saw a more serious look than his face had shown before. His eyes flashed a new understanding and awareness of the world that added to a new sense of his own purpose.

As sun lit upon his blond head, he looked different to me.

* * * * *

Erin Byrne writes articles and essays that dive deeper into travel, cultural and political themes. She has been writing since 2007. Her essays have won numerous awards, including Gold Solas Awards in 2010 and 2011 from Traveler’s Tales Best Travel Writing, and the Grand Prize at Book Passage Travel, Food and Photography Conference. Erin’s work has appeared in Everywhere magazine, World Hum, The Literary Traveler, Brave New Traveler, Traveler’s Tales, and a variety of other publications.

Erin lives with her family in the Seattle area. She is currently working on Wings From Victory, a collection of essays about Paris, and Catch the Live Current of the Artist, a book about Impressionist-era artists. A complete list of awards and links to Erin’s work can be found at www.e-byrne.com.

Photo credits:

Omaha Beach Cemetery: claydevoute

All other photos: Author