By Kristin Wegner

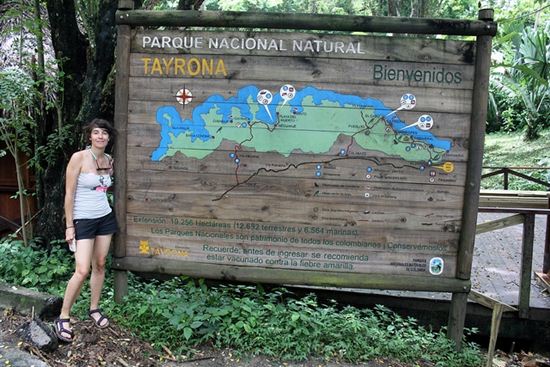

It was the fourth day of our trip and we were hopelessly lost in the jungle of Tayrona National Park, Colombia.

It was the fourth day of our trip and we were hopelessly lost in the jungle of Tayrona National Park, Colombia.

“I just don’t get how this happened,” Ben said, hovering on the boulder while lowering my backpack to me. I grimaced as I caught the straps, carefully maintaining my balance on two moss-covered stones while trying not to fall into the deep crevice between the rocks below me.

The land of Tayrona Park is said to be the heart of the universe by local indigenous wisdom. This should have reassured me. Yet after machete foraging our own path for the past few hours, we were far from the center of anything of which we were familiar. This was not the original plan I had for my little brother’s winter trip to visit Andres, my fiancé, and me in Colombia. Twenty-two, Ben was about to graduate from college in Chicago with a philosophy degree. Seven years his elder, I felt responsible to get him out of the natural jungle and back to the urban one.

“I mean, we saw the sign that said 90% there,” he said. All three of us remembered seeing the letrero sign marking the near completion of the walk to Pueblito. The last time we had seen the trail or any resemblance of a trail marker was more than five hours ago.

There’s something mythically magical about the equatorial sun, even more so when it’s pouring as what was described by Gabriel Garcia Marquez as years of downpours. The sublime yellow casts over the high mountains, through overhanging vine awnings, hitting puddles at the right angle to illuminate the crystal raindrops.

If we hadn’t been lost in the jungle, I would have appreciated the sun and the rain a bit more. I looked at Ben, not quite sure what to say in my older-sister role. He wore the same bandana over his hair that he had when he visited me in Colorado years ago. We had hiked then, too, on the well-groomed trails of Boulder, the summer before he went off to college.

Hundreds of red ants, bigger than my thumb, scurried on the sand mound next to us, carrying large green leaves in unison. A few hours earlier I had learned how much they hurt as they crept into my sandals, stinging the bottoms of my feet and ankles. I stared at the remaining red marks and struggled to think of reassuring words for Ben. Instead, I remained silent.

A few meters ahead, Andres was looking at his GPS that had mysteriously stopped working altogether at the legendary 90% sign. The arrow circled the screen spastically, neither indicating where we were nor where to go. He shook the handheld device a few times before putting it in his backpack.

A few meters ahead, Andres was looking at his GPS that had mysteriously stopped working altogether at the legendary 90% sign. The arrow circled the screen spastically, neither indicating where we were nor where to go. He shook the handheld device a few times before putting it in his backpack.

“Well, let’s continue another hour more,” Andres said. “We might be able to get to the highway outside of the park and bypass Pueblito altogether.” His words had a comforting feeling, but Ben and I were acutely aware that we were at the bottom of a valley and had already climbed two mountains since becoming lost.

Tayrona Park has the highest snow-capped mountain peak near an ocean, creating the greatest altitude difference in the world. When the bright blue sky is clear enough over the ocean, you can see the snow in the mountains less than a mile from the coast, a strange tropical phenomena that creates the perfect scenery for hiking adventures and lazy rainy afternoons under thatched roofs, sipping warm rum and playing cards.

We had slept in the comfort of hammocks in an abandoned beach lighthouse-turned-hostel the last three nights. Today was to be our last day in the park. Poring over maps the night before, opting not to backtrack through the well-traveled entrance route we arrived through, we calculated the trek out of the park via Pueblito to be four hours max. Since we planned to arrive at the airport in neighboring beach town Santa Marta by this evening, our supplies consisted of an almost empty jar of peanut butter and two bottles of water. We clearly did not expect this detour.

The park is believed to be a very powerful land, one that teaches the necessary lessons to foreign visitors and protects the remaining mountain indigenous communities — the present-day groups of the Kogi, the Arhuaco, the Wiwa and the Kankuamo modern-day children of the Tayrona. They refer to themselves as Western Civilization’s “Big Brother,” meaning we have much to learn from their knowledge.

To this day, women in the community maintain century-old traditions of weaving white clothes for the men and children. Married men wear cone-shaped hats to represent the snowcapped mountains. The concept of pristine attire in a rainforest baffled me, especially as the three of us were incapable of keeping anything we wore or kept in our backpacks unsoiled. Upon arrival a few days ago, we found ourselves hiking miles away from anything familiar, our feet sinking in mud and our clothes covered with red and brown splatters. As we struggled with our trek, decked out in modern camp gear, two bashful, giggling Kogi girls dressed in pristine white passed by, smiling at us curiously as we stopped to adjust our backpacks in the dense brush.

Growing up in the suburbs of Chicago, our mom would take us on different highways and back roads en route to our extracurricular school events throughout Illinois. She constantly told us that the only way to find your way and learn about an area is to get lost. I chuckled to myself, thinking about hours we spent lost in the car.

I couldn’t see more than four feet in front of me; I only trusted that Andres was ahead, making a trail with the machete. I could hear the whipping slash of palm leaves and vines, landing with a crash onto dense bushes and low flowers, hoping the trail he made would get us closer to the original trail.

I couldn’t see more than four feet in front of me; I only trusted that Andres was ahead, making a trail with the machete. I could hear the whipping slash of palm leaves and vines, landing with a crash onto dense bushes and low flowers, hoping the trail he made would get us closer to the original trail.

In the distance, we heard a coo of a bird. I quietly believed the call to be a shaman, guiding our hike to safety. The singsong voice fed us confidence as we continued on the trail.

“Hey, Kris, ya want more water?” Ben asked, gulping the last of his bottle. I silently grimaced. Of our three originally full bottles of potable water, we had polished off two of them since this morning. I heard a trickling stream in the background, but was curious how long it would be until we found access.

“Naw, thanks, kid,” I shook my head, pretending like I wasn’t thirsty, “ Go for it.” We looked at each other, his eyes piercing. I pretended like I wasn’t scared, but the little brother in him sensed my fear and knew to not pursue conversation. He glanced up at the top layers of the trees, choosing to comment on the beauty rather than the conflict of our situation.

“It’s just so green,” he said instead. We continued on the trail for another half hour, passing tiny multicolored hummingbirds as they zipped around the canopy and navigated through the trees.

The sun was almost covered by the mountain. We could barely see through the vines and shadows as we struggled to climb over boulders. Ben stood behind me, holding my backpack so I could duck under the huge branches that scratched my face as I maneuvered down the rocks. Andres held my hand, guiding my 6-foot descent down the boulder into a narrow crevice.

The sun was almost covered by the mountain. We could barely see through the vines and shadows as we struggled to climb over boulders. Ben stood behind me, holding my backpack so I could duck under the huge branches that scratched my face as I maneuvered down the rocks. Andres held my hand, guiding my 6-foot descent down the boulder into a narrow crevice.

Wham! Ben wacked me on the back.

“BEN!” I screamed, faltering before catching my footing and barely maintaining my footing on the rock.

“What? I was trying to kill a bug,” he said, calmly yet with a hint of “you’re paranoid, big sister” in his voice, the tone he uses to remind me that I’m turning into our mom as I near thirty years old.

“Look down,” I said. I pointed in front of me with one hand while holding Andres’ hand with the other. He peered in front of me, down the deep gage between rocks. As a group, we exhaled our near miss.

My mind started to play tricks with me, thinking of all the possible worst-case scenarios. Broken arms, poisonous bug bites, various subpar emergency rooms I’ve been to in foreign countries and the wilderness first-aid lessons I used to teach at a summer camp without proper firsthand experience. I started crying silently, clearly not in a position to continue climbing up and down individual boulders in a valley at dusk. I questioned how we were going to get out, what I was doing in Colombia, where we would sleep and why I had thought it was safe to bring Ben here. My thoughts went crazy and my body started shaking.

It was time to admit our defeat.

“Breathe. Calmly breathe,” Andres reassured me, looking at Ben trying to calm him as well. I sat on the rock, my feet dangled in the crevice.

“Breathe. Calmly breathe,” Andres reassured me, looking at Ben trying to calm him as well. I sat on the rock, my feet dangled in the crevice.

“This sucks,” I said, laughing through silent tears, listening to my breath slow down. “But there is nobody else in the world I’d rather be here with than you two,” I said. All three of us felt more confident.

Andres helped me down the boulder. As I slid my body down, we both noticed an eye-shaped carving on the side of the rock. Nestled atop two larger egg-shaped stones, the roof created a safe haven of jutted, stacked stones. We peered in ecstatically, grateful for something to protect us from the night rains. Andres crawled in the boulder-made cave first, using his flashlight as a guide. Ben went in second while I held the backpacks.

“It’s perfect,” Andres called up. I noted the relief in his voice. We looked at each other, hearing the faraway bird coo. I again imagined it was a shaman calling to us and telling us that we found safety.

Together, we brought our gear into the cave and Andres stuffed our backpacks, raincoats and even his sombrero into the cracks, creating a false floor over the huge crevice.

I sat on in between jutted rocks holding our most sacred items on my lap — Andres’ cell phone, a few candles, a flask from my Colorado friends and my pink water bottle. As Ben reached to hand me another candle, I accidentally dropped all of the items down the gaping hole. We could see our basic comforts at the bottom of the cave, but couldn’t reach them.

As it got darker, we lit our last candle, melted the wax at the bottom to make it stand up on the stone and sat on the rock with our legs dangling down the gaping hole. We passed spoonfuls of peanut butter and more swigs of water, wishing we had even a few drops of rum from the flask below our feet. We watched our shadows on the walls of Plato’s cave.

As it got darker, we lit our last candle, melted the wax at the bottom to make it stand up on the stone and sat on the rock with our legs dangling down the gaping hole. We passed spoonfuls of peanut butter and more swigs of water, wishing we had even a few drops of rum from the flask below our feet. We watched our shadows on the walls of Plato’s cave.

A sliver of moon rose, calling us to attempt to sleep for the night. My dreams were lucid and vivid; I had a vibrant feeling that something higher than us got us lost and that the bird’s call would continue to protect us.

The next day, we woke up with the sun. Ben scarfed down a few more spoonfuls of peanut butter and we passed the remaining drops of water around. As I climbed the first boulder, my arms and legs reminded me of the difficult terrain the day before, yet I was determined to get out.

Within minutes we were out of the boulders. Backtracking from yesterday, within a half hour we passed over the first mountaintop. Mystically, the hike that took us six hours to get lost in only took an hour to get out.

By 9 a.m. we found the original trail and heard voices in the direction of Pueblito. Before the sun had fully risen for the day, we were sitting on the porch of resident Park Guards on the outskirts of Pueblito. They served us steaming plates of yucca and fresh hand picked tangerines while telling us that they had heard us yelling the day before, but thought it was their shorthand radio.

We recounted our story — the bizarre GPS movement, the bird’s call, losing the trail at the 90% sign and the eye pictogram on the cave. The guards laughed, telling us that we were destined to get lost. We thanked them for breakfast by repaying them with our flashlights. Following the trail, we were out of the park by lunchtime.

We recounted our story — the bizarre GPS movement, the bird’s call, losing the trail at the 90% sign and the eye pictogram on the cave. The guards laughed, telling us that we were destined to get lost. We thanked them for breakfast by repaying them with our flashlights. Following the trail, we were out of the park by lunchtime.

Because we missed our flight back to Bogota we spent a few extra days at a fisherman’s beach town near Santa Marta. Ben and I drank cold beers overlooking the water, trying to make sense of the hike, the signs along the way and our lives.

Ben graduated from college the following May. He borrowed the bike I left at my parent’s house and headed south, where he found a Native American tribe to live with in Southern Illinois as autumn settled into winter. He learned about the sacred four directions from the community. Farther south, I live with Andres in Colombia, sometimes feeling just as lost as we were in Tayrona Park. Ben and I talk as often as we can. We still wonder how it happened, grateful for the eye pictogram on the cave and the bird’s call. I attribute the journey and adventure to our mom. I agree that the best way to navigate is to first get lost.

*****

Kristin Wegner is a modern-day pilgrim who loves to saunter with the trees. Originally from the Chicago area, her most recent homes were in Colorado and Colombia. Know more about Kristin in her blog.

*****

Photo credits:

Tayrona National Park: Eli Duke

Wiwa Indians inside Tayrona National Park: begonyaplaza

Exploring Tayrona National Park: Eli Duke

Leaf Cutter Ants: Micah MacAllen

Trekkers on top of boulders: Micah MacAllen

Stone Path to Pueblito: Micah MacAllen

Woman with Muddy Feet:Â Eli Duke