By Amber Parcher

The wind chimes were calling. Dozens of them, swirling in the soft April sun like butterflies dancing around a flower, waiting to be noticed.

The wind chimes were calling. Dozens of them, swirling in the soft April sun like butterflies dancing around a flower, waiting to be noticed.

I padded barefoot toward them across the wooden floor of the temple, forgetting that I’d left my dust-caked shoes at the front entrance.

It was the first of many times that I would be caught in the moment at Fo Guang Shan, a sprawling 55-acre Buddhist monastery in the middle of a bamboo forest at the base of a Taiwanese mountain range.

I was there on a weekend silent retreat aimed at introducing foreigners to Buddhism, getting a cultural and spiritual glimpse into this ancient religion and the monks and nuns who have forsaken modern life to abide by its teachings.

But mostly I was enjoying the wind chimes – until I spotted the tea.

A freshly brewed pot rested beneath the chimes on a splintering wooden table. I poured myself a cup of oolong and cuddled into a nearby plastic chair. About 20 feet below me, a monk was patting dirt around freshly planted pink carnations. But here, high up on this covered porch hugging a tiny temple in a remote corner of the monastery, there was no one but me. And the wind chimes.

A freshly brewed pot rested beneath the chimes on a splintering wooden table. I poured myself a cup of oolong and cuddled into a nearby plastic chair. About 20 feet below me, a monk was patting dirt around freshly planted pink carnations. But here, high up on this covered porch hugging a tiny temple in a remote corner of the monastery, there was no one but me. And the wind chimes.

A basket of crackers slid onto the table. I looked up. A monk, his head shaven and his gray exercise robes twisting around his slender body, smiled at me. He sat down across the table and poured himself a cup of tea. We shared it in silence, and then he stood up to water the flowers lining the porch railing.

Although I was the only visitor at his temple that morning, the monastics at Fo Guang Shan are used to guests. In fact, they welcome them.

Fo Guang Shan, Mandarin for “Buddha’s light mountain,” is an active monastery, inside its gates and out. More than 10,000 Westerners visited the previous year, and with relations warming between China and Taiwan, about 7,000 Chinese tourists tour it every month.

It’s the world headquarters for Humanistic Buddhism, a school that practices applying Buddha’s core principles to daily life. Humanistic Buddhism’s roughly 2 million devotees represent a relatively small fraction of the more than 360 million Buddhists in the world. But Fo Guang Shan’s reach stretches far. Its adherents come from 174 countries, and the monastery has 200 branches around the globe and an accredited university in California.

Its founder, Hsing Yun, whom the monastics call Venerable Master, set up shop in Taiwan after fleeing the communists in 1949 at the end of China’s civil war. Yun spotted a home for Buddhism in a religious culture that mixed Christianity, from the days of the Dutch colonists, with ancient Chinese Confucian philosophy and a Buddhism steeped more in superstition than in spirituality. He founded Fo Guang Shan in 1967, and except for a brief period in the late 1990’s, has made a point of opening its gates to visitors of all backgrounds.

Its founder, Hsing Yun, whom the monastics call Venerable Master, set up shop in Taiwan after fleeing the communists in 1949 at the end of China’s civil war. Yun spotted a home for Buddhism in a religious culture that mixed Christianity, from the days of the Dutch colonists, with ancient Chinese Confucian philosophy and a Buddhism steeped more in superstition than in spirituality. He founded Fo Guang Shan in 1967, and except for a brief period in the late 1990’s, has made a point of opening its gates to visitors of all backgrounds.

Today, Fo Guang Shan is Taiwan’s largest monastery. It houses more than a dozen temples, two Buddhist colleges (one for men and one for women), a children’s school, meditation rooms, a Japanese-style calligraphy hall, gardens and a recycling center.

Although it’s only a 30-minute drive east of Kaohsiung, Taiwan’s second-largest city and the island’s southern hub, Fo Guang Shan is psychologically a world away from the densely populated western coast that’s home to most of Taiwan’s 23 million inhabitants.

My trip to the monastery began on a Friday evening. Volunteers for Fo Guang Shan ferried our group – a mix of Swedes, French, Czechs, Americans, Canadians and Peruvians, all living in Taiwan – from Kaohsiung’s train station.

Nighttime is a fantastic time to arrive at the monastery. A 90-foot high golden Buddha crowned with red lights towers over the main entrance. Beneath him flashes a sign for a winding cave that looks like a distant cousin of Disneyland’s “It’s a Small World” ride. Inside, you walk alongside displays of animatronic monks and rainbow bridges meant to model the Pure Land, a sort of heaven for devoted Buddhists. Yun designed the cave in the 1970’s to attract visitors and introduce them to Fo Guang Shan’s school of Buddhism.

Under the red glow of the giant Buddha we met Venerable Miao Ming, a Canadian nun with a ginger-brown robe, a shaved head and a Type-A personality. She offered us candy and led a crash course on the fundamentals of Buddhism and the basic rules of monastic life. Our two-day, two-night stay was to be a swirl of meals, meditation, classes on Buddhism and free time to tour the grounds. We were to live by the monastics’ rules: No perfume, no makeup, no smoking or drinking alcohol on temple grounds, and we were to avoid wearing low-cut shirts and short-shorts. And all meals would be vegetarian.

Then it was off to our rooms and lights out by 11 p.m.

We were housed in a modest hotel within the monastery walls, with rooms for two, four and eight (and the unexpected bonus – or curse – of free WiFi in the lobby). Miao Ming and Austrian monk Hue Shou organize most of the trips for foreigners, who are invited to stay as long as they like.

There’s no set plan, but guests are encouraged to join in morning prayers (meaning 5 a.m. wake-up calls), mealtimes, evening meditation sessions and help the monastics with daily chores of sweeping the grounds or boiling pots of rice for the 400 monks and nuns who live on its hills.

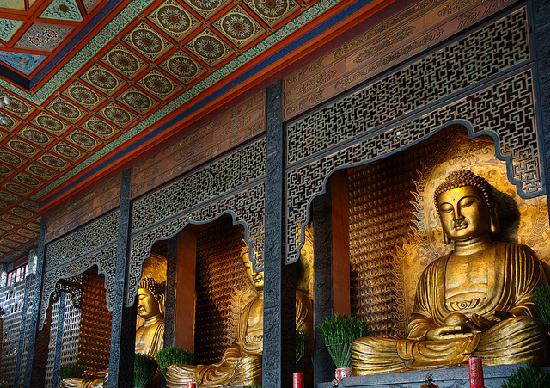

At 5:30 on Saturday morning, Miao Ming greeted us in the hotel lobby and lined us up double-file. No time for coffee; we were heading to the main temple to observe one of the monastery’s most important rituals: the day’s first prayers. We flowed alongside at least 100 monastics through heavy wooden doors into a tiled room filled top-to-bottom with miniature golden Buddha statues and a chandelier spilling from the ceiling like a lotus flower out of its pot.

The worshipers knelt on fraying red kneepads facing three 10-foot-high golden Buddhas on the far wall and silently waited for the sound of a gong that would begin their day.

The worshipers knelt on fraying red kneepads facing three 10-foot-high golden Buddhas on the far wall and silently waited for the sound of a gong that would begin their day.

As they chanted and twisted and turned, their cadence rising with the sun, their bodies folded over with foreheads kissing the floor, they looked like stones in a river, their billowing ceremonial maroon robes the water washing over them.

After prayers came breakfast. Meals are sacred affairs at the monastery and held in silence as active meditation. By 6 a.m., monastics on kitchen duty had set out food for 200 people in neat rows on long cream-colored tables: a bowl of white or red-bean rice, a steamed bun, a plate of cold seaweed and stewed potatoes and a bowl of warm soy milk to wash it all down.

When everyone had been seated on plastic chairs, the monks and nuns began an incantation that rose and fell in praise of and thanks to Buddha for the food about to nurture their bodies. We read along on English handouts next to our plates.

After breakfast, we drove around the monastery in golf carts as Miao Ming pointed out highlights of our upcoming solo three-hour silent tour of the monastery, which was to be the spiritual focus of the trip. Then we were given a map and free rein to wander around the buildings and grounds. We had no objective but simply to be. No to-do list except what our feet and heads decided. (Apparently mine wanted tea.)

Fo Guang Shan is large, weaving up and down several hills, with many hidden nooks to discover. At its core is the Main Shrine, where morning prayers take place, about a 60-step climb up from the main entrance and Pure Land Cave.

Fo Guang Shan is large, weaving up and down several hills, with many hidden nooks to discover. At its core is the Main Shrine, where morning prayers take place, about a 60-step climb up from the main entrance and Pure Land Cave.

On a forested hill above the shrine are two towering dormitories and the women’s college. To the left of the shrine are the iconic glowing Buddha and the men’s college. To the right and up yet another hill lies the children’s school and Great Practice Shrine, where I found my silent friend and tea.

I explored it all during my solitary tour, hours before busloads of mainland Chinese tourists arrive. Monks and nuns tending the grounds greeted each other and us with “Amitofo,” a Chinese transcription of Buddha’s name, which translates to “infinite life, infinite light.” As the sun started to heat up the paved streets, they tipped their hats closer to their heads and continued their chores.

I sat down beside a small fountain at the base of the Great Practice Shrine, out of breath from climbing a hill, and watched a nun sweeping leaves from the stones. As I wondered what she was thinking about, I realized that I enjoyed being in her presence without having to invade it. Her life was so very different from mine, but for the first time in my eight months in Taiwan, I didn’t feel like an outsider.

Twenty minutes later, I climbed more steps to the entrance of the temple. I slipped off my shoes and entered to light incense for the Buddha in the center, an offering of respect, before the wind stirred the chimes outside.

By 11 a.m., our group was breaking the silence over more tea to discuss our experiences. The overall consensus was that it was difficult to maintain a mindful state, even in such serene surroundings. Our thoughts turned too quickly from watching a bird hop along stones in a fountain to our e-mail inboxes. Miao Ming assured us that it was a battle that all but the most enlightened wage.

That evening, after a Chinese calligraphy class and dinner, we observed the day’s closing ritual.

Shortly before 10 p.m., two nuns perched on scaffolding on opposite sides of the Great Compassion Shrine, near the forest above the women’s college, in preparation for a melodious dance rooted more in Chinese than in Buddhist tradition. One rang a silver gong meant to symbolize rain to cultivate crops. Another glided a log into a large bell, creating a deep vibration that reverberated through the trees, through the monastery’s walls and, according to Chinese tradition, into the depths of Hell, where its sound is said to give tortured souls momentary peace.

Shortly before 10 p.m., two nuns perched on scaffolding on opposite sides of the Great Compassion Shrine, near the forest above the women’s college, in preparation for a melodious dance rooted more in Chinese than in Buddhist tradition. One rang a silver gong meant to symbolize rain to cultivate crops. Another glided a log into a large bell, creating a deep vibration that reverberated through the trees, through the monastery’s walls and, according to Chinese tradition, into the depths of Hell, where its sound is said to give tortured souls momentary peace.

The rest of the weekend was more relaxed. On Sunday morning, before our last scheduled meditation, we ate a buffet breakfast in a less formal dining hall designated for visitors. Our group openly broke our vow of silence and chatted away, mostly in English. Miao Ming joined us, answering all our questions about Fo Guang Shan and monastic life.

She explained that everything the monastery does is designed to propagate Buddhism, but it’s all a gentle push. Their method is to simply let people enjoy their stay and hope that for some, a pleasant experience will trigger a deeper need for spirituality. Monastics, she said, understand that Buddhism isn’t something that can be forced. Rather, it must be found.

Sort of like a pot of tea beneath some wind chimes.

*****

Amber Parcher is an international journalist just returning from a year in Taiwan as The Washington Post’s special correspondent. She now manages a newspaper’s website in Boston and freelances for National Geographic’s travel blog, the Christian Science Monitor and does regular radio contributions for London-based Monocle Magazine’s online radio station. Follow her on Twitter @amberparcher.

*****

Photo credits:

Golden Buddha: Craig Loftus

Tea: Dimitri Fedorov

Master Hsing Yun: miheco

Three Buddhas: Craig Loftus

Fo Guang Shan monastery: Craig Loftus

Chinese Wind Chimes: Steve Webster