By Candice Wynne

It wasn’t the sight of blood that bothered me as much as the thought of hearing the animals scream. That was the first horrific image that sped through my mind when my guide, Ram, asked me if I’d be interested in attending a sacred Hindu ceremony held every Saturday in Pharping, a little town about an hour’s ride from Kathmandu, Nepal: a ceremony where chickens, goats and pigs would be sacrificed to the ferocious mother goddess, Kali.

It wasn’t the sight of blood that bothered me as much as the thought of hearing the animals scream. That was the first horrific image that sped through my mind when my guide, Ram, asked me if I’d be interested in attending a sacred Hindu ceremony held every Saturday in Pharping, a little town about an hour’s ride from Kathmandu, Nepal: a ceremony where chickens, goats and pigs would be sacrificed to the ferocious mother goddess, Kali.

“Of course,” Ram said, looking me straight in the eye, “if you want to experience the real Nepal, you won’t want to miss the animal sacrifices at the temple of Dakshinkali.”

I had arrived in Kathmandu on March 14, 2002, and early the next morning I set out to find Durbar Square in the heart of the ancient city. Not ten minutes after I set foot onto this UNESCO World Heritage site, a handsome young Nepali man dressed in Western clothes approached me. He offered his hand politely and introduced himself, producing his official laminated license to act as guide. He must have spotted me as soon as I stepped onto the square, correctly assuming that I was another mystified Western tourist.

While introducing myself and asking a few questions, I made a mental checklist of all the potential risks and benefits of accepting this stranger’s offer. When traveling in foreign countries (particularly as a single woman) there is always an element of risk, of the unknown, and the risk increases when traveling in developing countries like Nepal. Because the level of poverty is so severe, there is a greater chance this will take precedence over someone’s otherwise high moral code; however, since Durbar Square was a public place, the risk of anything untoward happening was relatively slim and I knew the company of a local would enhance my experience a hundredfold.

I smiled at him and asked how much his services as my guide for the day would cost. Ram waved his hand in the air, dismissing the worldly issue of money, saying I could decide the amount when the day was done. If I liked his services, I could pay him whatever I felt he was worth. I wasn’t used to doing business in such an ambiguous manner, but I agreed and we set off for the next five hours, exploring the ancient wonders of Durbar Square.

I smiled at him and asked how much his services as my guide for the day would cost. Ram waved his hand in the air, dismissing the worldly issue of money, saying I could decide the amount when the day was done. If I liked his services, I could pay him whatever I felt he was worth. I wasn’t used to doing business in such an ambiguous manner, but I agreed and we set off for the next five hours, exploring the ancient wonders of Durbar Square.

It was when we stopped for lunch that Ram posed his question about the excursion to Pharping. Getting to the entrance of The Top Garden restaurant was an adventure in itself. It was located on – you guessed it – the top floor of an old building, only steps from Durbar Square. Ram proudly informed me we would be ascending to the top of the building using Nepal’s oldest elevator. Terrific. As we stepped inside the tiny dark enclosure, Ram pulled an old metal gate closed in front of us and then pushed a button for the fifth floor. As it slowly chugged and rattled its way up, I tried to imagine how my obituary would read if we perchance didn’t make it out alive: something quite unbecoming like “Shafted in Nepal.”

We eventually made it to the fifth floor, and then had to climb up two flights of stairs to an open-air restaurant with a view of the city. Ram ordered something called Buff Momo and I ordered a tuna sandwich and a Coke: safe and predictable. In my defense, I should mention that on my last day in Kathmandu, I threw caution to the wind and ordered Buff Momo for myself, only to discover it was a plate of small dumplings filled with minced water buffalo meat (and probably hooves, tongue and bone). Unremarkable and apparently cooked long enough to preserve my delicate American digestive system.

Okay, so I’d known Ram for half a day and he wanted me to leave the relative safety of Kathmandu and travel with him to some tiny village miles outside the city, a place I’d never heard of before. It could be fictitious. Ram was filled with boyish enthusiasm, casually explaining that Saturday was the best day to visit the temple of Dakshinkali, saying thousands of Hindu pilgrims would be gathered there to worship Kali.

My immediate mental reaction was: Are you out of your mind? No way! I might be foolishly putting myself in harm’s way, about to be turned over to the infamous Maoists and held for ransom, or sold for body parts – or even worse – well, let’s not even go there. It wasn’t completely unreasonable to imagine that I was about to step off the face of the earth and never be heard from again. Everything I’d ever been taught about traveler’s safety was shouting at me to turn around and hightail it the other way. But there was something (like a tiny cartoon devil standing on my shoulder) that sounded so intriguing about Ram’s proposal.

My immediate mental reaction was: Are you out of your mind? No way! I might be foolishly putting myself in harm’s way, about to be turned over to the infamous Maoists and held for ransom, or sold for body parts – or even worse – well, let’s not even go there. It wasn’t completely unreasonable to imagine that I was about to step off the face of the earth and never be heard from again. Everything I’d ever been taught about traveler’s safety was shouting at me to turn around and hightail it the other way. But there was something (like a tiny cartoon devil standing on my shoulder) that sounded so intriguing about Ram’s proposal.

I also couldn’t dismiss the underlying reason why I’d decided to take this journey in the first place, thousands of miles and worlds away from my home in California. I had set out with a clear intention and a personal mantra: Now is the time to leave all my normal behind and step out on the Edge. Sure, I wanted to get back home alive and well, but I had this wild craving to roll around in the dirt a little. I wanted to taste it. The Universe has a wicked sense of humor, rarely letting us get away with idle promises. With this wildly absurd invitation now before me, I knew my mantra was being put to the ultimate test.

In anyone’s estimation, the proverbial Edge was breathing right down my little white neck. The idea of witnessing innocent animals being slaughtered sounded completely terrifying and uncivilized, but I also didn’t want to miss this rare opportunity to immerse myself in a culture so different than my own. If I were to do this, I would have to put my Western notions temporarily aside, far aside.

“Okay, Ram, you’ve got it. I’ll go with you to Pharping tomorrow.”

He seemed quite pleased and said that he would be at my door at 8:30 in the morning, and then he just waved good-bye and walked away. I wandered back to my hotel and unlocked the door to my room (heavy bars on the windows), and as I stared out to the street below I thought: Candice, are you totally insane? What the hell did you just commit to?

He seemed quite pleased and said that he would be at my door at 8:30 in the morning, and then he just waved good-bye and walked away. I wandered back to my hotel and unlocked the door to my room (heavy bars on the windows), and as I stared out to the street below I thought: Candice, are you totally insane? What the hell did you just commit to?

I quickly dug out my Lonely Planet guide and to my great relief there was actually one whole page devoted to Dakshinkali. It read like the intro to an Indiana Jones movie:

At the southern edge of the valley, in a dark, somewhat spooky location in the cleft between two hills and at the confluence of two rivers stands the bloody temple of Dakshinkali. The temple is dedicated to the goddess Kali, Shiva’s consort in her most bloodthirsty incarnation, and twice a week faithful Nepalis journey here to satisfy her bloodlust. The four-armed main image of Kali in the temple is of black stone and she tramples upon a male figure.

Saturday is the major sacrificial day of the week, when a steady parade of buffaloes, chickens, ducks, goats, sheep and pigs come here to have their throats cut or their heads lopped off. Oh god. Now all I had to do was pack my camera, leather whip and anti-venom kit, and I’d be set to go.

Ram arrived on time Saturday morning with his cousin, Chandra, who would serve as our driver for the day. As I stepped out to the waiting car, Chandra stood next to it, grinning and proudly polishing its red spray-painted and dimpled exterior with a dirty rag. Heading out, I couldn’t believe the chaos of the traffic where every two minutes there was a near collision. After an hour of this terrifying carnival ride, we arrived in Pharping and pulled into a huge parking lot filled with dusty cars and buses. Hundreds of people were making their way toward the entrance to the temple.

Stepping out of the car, something told me that my world was about to be tweaked. There was no denying that I was peering over precipice of my comfort zone. Ram led me through the crowd, over footpaths that wound around the complex, over a murky pond and down a small hill. We passed a long open-stall market where vendors were selling garlands of yellow marigolds and lengths of gauzy red fabric. I imagined I would see a lot of Hindu devotees, but I wasn’t prepared for the masses of people lined up two and three deep, patiently waiting their turns to enter the roofless, outdoor temple. I saw speckled chickens held snugly under their owner’s arms and wide-eyed goats being pulled along by the ropes around their necks. It wasn’t until Ram led me up a small embankment above the temple that I got my first chance to see what was really going on.

Stepping out of the car, something told me that my world was about to be tweaked. There was no denying that I was peering over precipice of my comfort zone. Ram led me through the crowd, over footpaths that wound around the complex, over a murky pond and down a small hill. We passed a long open-stall market where vendors were selling garlands of yellow marigolds and lengths of gauzy red fabric. I imagined I would see a lot of Hindu devotees, but I wasn’t prepared for the masses of people lined up two and three deep, patiently waiting their turns to enter the roofless, outdoor temple. I saw speckled chickens held snugly under their owner’s arms and wide-eyed goats being pulled along by the ropes around their necks. It wasn’t until Ram led me up a small embankment above the temple that I got my first chance to see what was really going on.

The temple of Dakshinkali is not what we think of a typical temple, but an open plaza about 60 feet square with a solid floor of white marble. There is a three-foot-high railing of brass and steel around the perimeter and a small gate where devotees enter with their live sacrifices. Along one side is a shrine with an idol of the four-armed deity, Dakshin Kali. She is carved from black stone, fearlessly standing on a male figure lying helpless on the ground.

Ram explained that devotees believe their prayers will be answered only after Kali accepts their sacrifice. Some examples of the prayers he mentioned sounded similar to ones I’ve heard at home: Help me pass my entrance exams… Please preserve the health of my child… Bless me to win the lottery.

From the shrine, the people patiently moved along to a point just below where I was perched. A short horizontal structure ran the length of one side of the plaza where the actual sacrifices took place and its low roof functioned as the surface for cutting the heads off chickens. The people were dressed conservatively as they brought their animals to one man, who I assumed was the executioner. The owner of the animal handed over his chicken or goat to this man and with one deft swipe of his knife, it was all over. In fact, it was so quick that the moment between life and death was less than a second, allowing no chance for the animals to scream or squawk–nothing auditory to mark the end of a life.

Some psychological defense must have kicked in because any fear or squeamishness I had previously held just disappeared. I became completely engrossed in this great throng of Hindus performing an ancient ritual. This ordeal was a weekly occurrence for these Hindus and they were all there with the very same faith in Brahma, Shiva, Vishnu and Kali as much of the Western world has in God and Jesus. As the din of the crowd continued uninterrupted, my initial worries about hearing the death screams subsided.

My focus sharpened as a man approached the executioner with a white goat in tow. Three men stepped in and held it to keep it still. They paused before continuing with the act, appearing intent on carrying this through with the least amount of trauma. Given the situation, this must sound absurd, but that’s the impression I got. As soon as all four men braced themselves, the executioner took his knife and slit the animal’s throat with one stroke. The bare feet of the devotees were covered in the blood of the slaughtered, the floor of the temple awash in red. Hundreds of voices mingled with the constant clanging and chiming of brass bells, sending me into a semi-hypnotic state. Add the heady aroma of Nag Champa incense mixed with bodies and dirt and blood, and for a moment my whole world took a detour down the rabbit hole.

My focus sharpened as a man approached the executioner with a white goat in tow. Three men stepped in and held it to keep it still. They paused before continuing with the act, appearing intent on carrying this through with the least amount of trauma. Given the situation, this must sound absurd, but that’s the impression I got. As soon as all four men braced themselves, the executioner took his knife and slit the animal’s throat with one stroke. The bare feet of the devotees were covered in the blood of the slaughtered, the floor of the temple awash in red. Hundreds of voices mingled with the constant clanging and chiming of brass bells, sending me into a semi-hypnotic state. Add the heady aroma of Nag Champa incense mixed with bodies and dirt and blood, and for a moment my whole world took a detour down the rabbit hole.

This was powerful stuff and I realized the singularity of this moment in my life. Up to this point, only world travelers with exotic lives and big budgets had experiences like this. I was no longer just reading about this kind of stuff, I was smack dab in the middle of it. This was as far from my normal as I would ever get.

All of a sudden, Ram politely excused himself, disappearing down the path before I could protest his hasty exit. As soon as I realized I couldn’t see Ram or even spot him in the crowd, my mind entertained notions of desertion. How could he just leave me like this?! Two voices began arguing inside my head: He could walk away and never return and I’ll be left to fend for myself… It could be days before I make it back to my hotel in Kathmandu, no telling in what condition… Noooo, he wouldn’t do that… I trust him, he’ll be back any second now. Any second. When he returned fifteen minutes later, smiling meekly and toting a bag heavy with goat meat, I tried to hide how petrified I had been.

When Ram said it was time to go, I really wanted to stay longer, but it wouldn’t have been polite to argue. On the way back to the parking lot, endless lines of people continued to weave their way down to the temple. We passed several vacant-eyed beggars kneeling on the ground, waving metal or plastic bowls in the air. I dropped a few coins into several of them and noticed that each bowl held a meager amount of uncooked rice. It was difficult to come to grips – as someone from a land so abundant – with the notion that going home with fifty cents and a cupful of rice was a good day. Slowly, we made our way back to Chandra, who was waiting patiently next to his marvelously imperfect red car. Ram opened the trunk to deposit his purchase and we drove off, winding back through the little valley to Kathmandu.

When Ram said it was time to go, I really wanted to stay longer, but it wouldn’t have been polite to argue. On the way back to the parking lot, endless lines of people continued to weave their way down to the temple. We passed several vacant-eyed beggars kneeling on the ground, waving metal or plastic bowls in the air. I dropped a few coins into several of them and noticed that each bowl held a meager amount of uncooked rice. It was difficult to come to grips – as someone from a land so abundant – with the notion that going home with fifty cents and a cupful of rice was a good day. Slowly, we made our way back to Chandra, who was waiting patiently next to his marvelously imperfect red car. Ram opened the trunk to deposit his purchase and we drove off, winding back through the little valley to Kathmandu.

At my hotel, I thanked Ram for his superb work as my guide and handed him about 25 dollars, his mouth turning into a wide grin. In my room, I sat down and began to unwind, to contemplate the events of this amazing day. Yes, I had witnessed innocent animals being slaughtered and sacrificed to a bloodthirsty Hindu goddess. Yes, my ears were ringing with the sounds of honking horns and chiming brass bells – my lungs breathing in the chaos permeating the air. Yes, I had stepped across a boundary most would be too fearful and timid to cross. I had peered over the Edge and I would never look back.

*****

Candice Wynne spent decades traveling the gauntlet of her life when one day she decided it was time to step across the threshold of conventionality to discover the wonder of traveling the world one country, one train ride, one curious footstep at a time. She holds an MFA in Narrative Nonfiction at San Jose State University, California.

*****

Photo credits:

Dakshinkali Shrine: Simonetta Di Zanutto

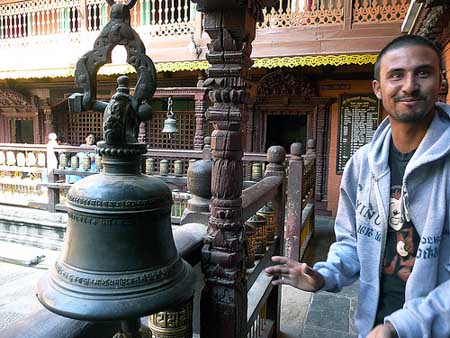

Nepali Guide at Durban Square: Cheryl Marland

Durbar Square: dalbera

Pharping Nepal: Lyle Vincent

Queue at Dakshinkali Temple: Yutaka Fujiii

Dakshinkali Chicken Offering: Yutaka Fujiii

Female Tourist at Durbar Square: amanderson2