By Alli Ockinga

The late December air scratches my lungs like sandpaper as I emerge from Bupyeong Station. I expel clouds of breath that stand out white against the blackened sky and look enough like the real thing that I half expect snowfall. I handle a small parcel in my purse, a gift from my friends Michelle and Hannah, an American couple who, like me, are here teaching English as a second language. It’s a novel, and I’m excited to read the first chapter tonight–but only that. English stories are a rare and special treat for me, for they are not much available here. I don’t want to waste the pleasure all in one evening.

The late December air scratches my lungs like sandpaper as I emerge from Bupyeong Station. I expel clouds of breath that stand out white against the blackened sky and look enough like the real thing that I half expect snowfall. I handle a small parcel in my purse, a gift from my friends Michelle and Hannah, an American couple who, like me, are here teaching English as a second language. It’s a novel, and I’m excited to read the first chapter tonight–but only that. English stories are a rare and special treat for me, for they are not much available here. I don’t want to waste the pleasure all in one evening.

I extend my hand to hail a cab. My fingers are frozen. Too late, I realize I’ve left my gloves on the subway, which is already looping back to Seoul by now. I reach eagerly for the door when a cab pulls over. But when the driver takes a look at me, he decides he can’t be bothered with a waegook: an outsider. He issues me a baleful glare and waves me away like a mule swishing aside the unwelcome attentions of a fly. Discrimination of this sort used to offend me. Now, though, I accept the minor inconvenience and step a little further into the stream of traffic, determined not to be ignored.

A second cab stops, and the driver allows me into the back seat.

“Ah-ahnyo-ung has-s-seo,” I say, my chattering teeth making me stumble over the greeting.

“Mm,” the driver replies. Damn. Now he thinks I’m stupid. It doesn’t really matter, because in a metropolitan area of this magnitude, the odds of seeing him again are literally less than one in a million. Still, it’s nice to make a good impression. He glances at me in the rearview. “Meegook sarim?”

“Mm,” the driver replies. Damn. Now he thinks I’m stupid. It doesn’t really matter, because in a metropolitan area of this magnitude, the odds of seeing him again are literally less than one in a million. Still, it’s nice to make a good impression. He glances at me in the rearview. “Meegook sarim?”

“Nae,” I say. Yes, I’m American.

“Mm.” And that is the end of that. We drive in that not-quite-companionable silence of public transit to my apartment block, where he wordlessly accepts the nominal cab fare.

“Ka-riss-uh-mus chal bo-naeyo,” I say in farewell. Happy Christmas.

Upstairs in my apartment, I step onto the frigid tiles of my balcony and regret the no-shoes-inside rule of this nation all over again. From my sixth-storey perch, I gaze on the bustling convergence of streets, businesses and people that make this neighborhood, if not yet home, then at least a place less foreign than the rest.

I can see the concrete square where little boys trade Pokemon cards on Saturday mornings and the red-and-white striped awning of the family-run seafood stall, with its assortment of cephalopods and nameless-to-me aquatic creatures. One of the brothers seems to believe his life mission is to sell me fresh starfish. “Stars very many delicious!” he insists. “You, stars eating.” My definition of food has expanded considerably since moving to The Land of the Morning Calm. Maybe someday before I leave I’ll give in. I can’t tell if he’s working tonight. All the brothers look the same from up here. At any rate, they’re closing down. One young man climbs onto a bicycle that would be considered vintage at home and pedals around the corner.

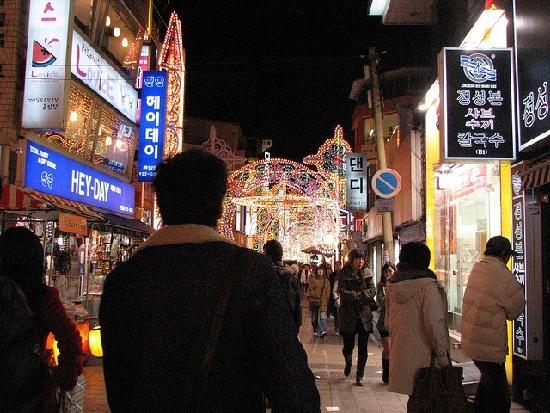

The lights and buzz of three or four dozen neon signs illuminate the whole neighborhood under a manufactured Aurora whose glow advertises everything from drinking establishments to shoe repair shops. Pop music wafts from nearly every doorway, underscoring the cacophony of this wildly populated city. Living in South Korea is rather like living inside a giant pinball machine, and suddenly, the view makes me very tired.

The lights and buzz of three or four dozen neon signs illuminate the whole neighborhood under a manufactured Aurora whose glow advertises everything from drinking establishments to shoe repair shops. Pop music wafts from nearly every doorway, underscoring the cacophony of this wildly populated city. Living in South Korea is rather like living inside a giant pinball machine, and suddenly, the view makes me very tired.

I turn back inside. When I moved in, the walls were bare, the bed unslept, the bureau empty. I hung up letters from friends and pictures of my family from that other world. But slowly, bits of my present experience have leaked into my space. Above the bed hangs a traditional child mask from Insadong, my favorite district in Seoul. On the nightstand sits a fist-sized white-and-yellow striped seashell that I found while exploring an island off the eastern Korean coast. And on the wall opposite my mirror are the belts I have earned through studying the traditional Korean martial art of hapkido. White, yellow, green, blue, brown, red. When I earned my first belt, my Master teased me, saying, “You, nine percent Korea-person.” I have my black belt test next month. He says that if I pass the test, I will be twenty percent Korean.

And in the corner sits a bamboo stand, under which three shiny packages lie. Christmas presents from my family. I should open them, but I don’t. When I do, Christmas will be over. I’m not ready for that yet.

It’s not as if Christmas snuck up on me this year. If anything, I was overly aware of its approach since I had to do my holiday shopping well before Thanksgiving to get the packages home on time. If that wasn’t enough, my kindergarten students reminded me every half an hour.

It’s not as if Christmas snuck up on me this year. If anything, I was overly aware of its approach since I had to do my holiday shopping well before Thanksgiving to get the packages home on time. If that wasn’t enough, my kindergarten students reminded me every half an hour.

“Alli-sam! Alli-sam! Alli-sam!” they’d chant with puppy-like enthusiasm as they affixed the token sign of respect to my name.

“What, what, what?” I’d say, knowing full well what.

“This month Ka-riss-a-mus!” Hangul, the language of Korea, is quick and choppy, with each phoneme afforded its own time slot and spit out like keys on a typewriter. Ka-riss-uh-mus.

“Yes, it is!” I replied every time. “Do you know how many days it is until Christmas?”

“Twelventy.”

“Almost.” Season of giving or not, I was still their teacher. “Think. What comes after eleven?”

“Twelb! Twelb days Ka-riss-a-mus!”

Furthermore, as if the hourly reminders aren’t enough, I have been assaulted with the kind of unrelenting and gaudy holiday cheer especially reserved for department-store windows. It is the worst at Lotte Mart, a three-storey superstore that hawks every imaginable ware, and some unimaginable ones too. Stingray jerky, for example. At the Lotte Mart, men extol the virtues of foreign produce into microphones while young women dressed, inexplicably, in cheerleader skirts force samples of fish into my hands for inspection. Little girls and boys that have never seen Caucasions see me and cower behind the legs of their parents, pointing. By this time, I’ve become accustomed to the catcalls and the still-present remnants of a market-based society, but I wasn’t prepared to see how the Lotte Mart approached the Christmas season with the same ferociousness.

Each window of the Lotte Mart is dedicated to a different Christmas cliché: in one, Rudolph balances a blinking crimson beach ball on his nose while a young doe wearing leg warmers and high-heels watches from the stretched-cotton snow bank. Another window features a garish Santa trying to squeeze down a chimney while his elf looks on in disapproval, holding diet pills in his outstretched hand. A final window hosts a pair of gold foil trees draped in an arresting shade of pink tinsel and flashing blue lights. It is all a little difficult to digest. From just about any vantage point in my suburb, I can see no less than five glowing red crosses indicating Christian churches. Even Jesus is neon here.

Each window of the Lotte Mart is dedicated to a different Christmas cliché: in one, Rudolph balances a blinking crimson beach ball on his nose while a young doe wearing leg warmers and high-heels watches from the stretched-cotton snow bank. Another window features a garish Santa trying to squeeze down a chimney while his elf looks on in disapproval, holding diet pills in his outstretched hand. A final window hosts a pair of gold foil trees draped in an arresting shade of pink tinsel and flashing blue lights. It is all a little difficult to digest. From just about any vantage point in my suburb, I can see no less than five glowing red crosses indicating Christian churches. Even Jesus is neon here.

At any rate, I’m not contributing much to the culture of Christianity in Korea. In my twenty-four Christmases, this is the first time I’ve not been to church, because it’s the first time I don’t have my mother around to appease. I wonder how Koreans have managed to avoid turning Buddha’s birthday into this kind of circus. But then I wonder if these displays are really so different from those featured in the less-reputable department stores in America.

Probably not. It’s just that the physical distance from home has magnified the differences tonight. There’s no snow here, for one thing. We’ve had a couple dustings, but it’s nothing like the thigh-deep mess I’m used to. I haven’t made my harrowing journey back home from Idaho, a six-hour trip made perilous by tortuous back roads painted slick with black sheets of ice. I haven’t faced Mom’s reproving looks at my ratio of rum to hot butter mix, nor have I suffered through thirteen consecutive screenings of Ralphie showing how the piggies eat. There won’t be any strange but welcome run-ins with old friends on last minute shopping runs. And Father Tom at St. Joseph’s parish, who somehow manages to make even Christmas a heavy-hearted affair, won’t be insisting we forsake thoughts of shiny-papered packages beneath our trees. As to that, I didn’t get to see Dad struggle to put up the tree this year, muttering decidedly un-Christmasy words beneath his breath.

It certainly doesn’t feel like Christmas without incessantly arguing with my three siblings about ornament placement, which has always been an issue of particular contention in our household. My younger brother lacks the spatial awareness to place the heavier ornaments near the trunk, while my older brother refuses to throw away the homemade ornaments from our schooldays, six or seven of which Mom has secretly been tossing each year in her quest for “just once, a really nice Christmas tree.” She thinks we don’t know. And they all think I’m too bossy. “Little Miss Perfect,” my sister ought to be sneering, right about now. “Who never does any tiny little thing wrong, ever.”

It certainly doesn’t feel like Christmas without incessantly arguing with my three siblings about ornament placement, which has always been an issue of particular contention in our household. My younger brother lacks the spatial awareness to place the heavier ornaments near the trunk, while my older brother refuses to throw away the homemade ornaments from our schooldays, six or seven of which Mom has secretly been tossing each year in her quest for “just once, a really nice Christmas tree.” She thinks we don’t know. And they all think I’m too bossy. “Little Miss Perfect,” my sister ought to be sneering, right about now. “Who never does any tiny little thing wrong, ever.”

I remember trying to escape Tree Decorating Night as a teenager. I wanted to run off to a party where someone’s parents had left Schnapps or to indulge in mistletoe-inspired mischief with my boyfriend. Back home, there was always somewhere else to be.

Now I am there: somewhere else. I think about calling home, but I glance at the clock and remember that I live seventeen hours in the future here. It is sometime in the painfully early morning of yesterday for them. That means they have already celebrated Christmas Eve. I push the thought away, heading to the kitchen to stir up some dinner. The golden rule of a traveler is not to think too much about home, because then you might want to go back.

I am aware, of course, that my situation is not particularly unique. Millions of displaced people all over the world are in this position, fighting wars or sending back money or simply fulfilling dreams that justify the lonesome nights. This is the tradeoff.

A short time later, I sit cross-legged on the floor with my meal of steamed dumplings, kimchi and rice. In the apartment next door, someone practices piano with a tentative and unskilled hand. The tune is just out of reach, but it seems somehow familiar. I stop chewing and listen intently. The music stops, then starts again, and this time, encouraging voices join in.

A short time later, I sit cross-legged on the floor with my meal of steamed dumplings, kimchi and rice. In the apartment next door, someone practices piano with a tentative and unskilled hand. The tune is just out of reach, but it seems somehow familiar. I stop chewing and listen intently. The music stops, then starts again, and this time, encouraging voices join in.

And suddenly there it is: Through the years, we all will be together, if the fates allow…

It’s in Korean, but there’s no mistaking it. The family next door is singing Christmas carols. I wonder if their whole family is there, or if they are missing someone, too. And it strikes me that the experience of being human isn’t all that drastically different from one continent to the next. We celebrate when we can, mourn when we must, and try not to mess things up too badly in the meantime. We may be speaking different words, but in essence, we’re all singing the same songs.

And with that pleasing thought, I reach for the first package under my Christmas bamboo stand.

*****

Alli Ockinga is a writer who indulges her passion for international travel whenever possible. When not nurturing a piece of writing, she can be found tending her garden or trying out a new artistic medium. Alli lives in Seattle with a young rabbit named Jameson. Find out more about Alli in her website.

*****

Photo credits:

Christmas Seoul City Hall: Ming-yen Hsu

Seoul taxi driver: James Cridland

Seoul by night:Â Philippe Teuwen

Christmas gifts: Jennifer C.

Seoul Street Christmas: Marie

Tree decorating: Britt Reints

Friends in Seoul at Christmas: Chelsea Hicks