by Joel Carillet

For hours I had been traveling up the Nile Valley, from Luxor to Cairo, on a train jammed full of Egypt’s working poor. Having been one of the last to board, I had no choice but to take one of the worst seats. So along with maybe a dozen other men I sat scrunched in the rear of the car and on the floor, my chin resting on my knees.

For hours I had been traveling up the Nile Valley, from Luxor to Cairo, on a train jammed full of Egypt’s working poor. Having been one of the last to board, I had no choice but to take one of the worst seats. So along with maybe a dozen other men I sat scrunched in the rear of the car and on the floor, my chin resting on my knees.

The train followed the route of the world’s longest river, the Nile. Egypt had once been a great civilization on account of the Nile’s gifts of water and silt, and still today the river is why Egypt can sustain a population of 80 million people — the largest in the Middle East. Without the Nile Egypt couldn’t exist, just as none of us could exist were it not for the unmerited blessings we regularly receive.

At 1:00 a.m. I reached Cairo and took a taxi to Tahrir Square, the city’s central hub. I was hungry and, having been to Cairo before, knew that while most of the city was closed down at this hour, a couple fast food restaurants would be open here.

The taxi dropped me off across the street from Hardee’s. A moment later, just as I was about to open the restaurant door, two street children pounced on me with plaintive cries for food. Had the square been dense with cars and people and noise, I probably wouldn’t have noticed them so clearly.  But now it seemed there were no people in all of Egypt except these two boys and myself, standing together in the chilly January air.

Being a veteran traveler as well as having once lived in Egypt for a year, I was no stranger to people asking me for help. But seldom had I been so moved by the sincerity of the person’s plea. In my broken Arabic I asked when they had last eaten–about sixteen hours ago, they said–and then I turned to look through the window beside us. For the boys, to look through this window was to gaze upon a world inaccessible to them; for me, it was to see familiar and easy ground. I turned back to the boys and asked them to wait while I went inside to buy them food. Since I myself was traveling on a tight budget and was even skipping meals on occasion, part of me identified with the children’s hunger. But mostly, the children reminded me how rich I really was.

and asked them to wait while I went inside to buy them food. Since I myself was traveling on a tight budget and was even skipping meals on occasion, part of me identified with the children’s hunger. But mostly, the children reminded me how rich I really was.

At the counter I ordered two hamburgers. Then, as the burgers were being cooked, I overcame my remaining stinginess and bought them one of Hardee’s delicious, big chocolate chip cookies, figuring they could split it.

When their food was ready I walked back outside and invited them in to eat with me. “No!” they cried, terror-stricken. “We do not belong in such a nice place!” Unable to persuade them otherwise, I brought the food out, and as they took the burgers they showered me with thirty seconds of nonstop blessings, praying that Allah would bless me always. After they finished their moving display of gratitude, I reached into the bag and pulled out the cookie, extending it for them to take. Both boys feel silent now and tears welled up in their eyes as they insisted this was too much. They refused the cookie six times.

I knelt down beside them, looked into their eyes, and marveled at what was before me:Â two destitute boys who asked only for what they needed, unwilling to take a crumb more.

Still on my knees, I spoke with the same sincerity with which they had refused the cookie. “Please,” I said, “take this cookie. It is yours now, not mine.” And on this seventh attempt, after a long and silent pause, they held out their hands and took the cookie.

I had seen many wonders in Egypt–the Pyramids, the Aswan High Dam, the Temples of Karnak, the Valley of the Kings, the treasures of King Tut. But it was this scene outside Hardee’s that left me truly awestruck, for here I found people who, amidst their grubby poverty and outcast existence, witnessed to me, a rich man from the West.

The events of that night are now in the past, but there are moments when I’m transported back to that empty square and to the earnest faces of two boys who, upon receiving a simple burger, took to praising God, and to praising me. I’m reminded of them, for example, when I’m in church and hear again the story of a Pharaoh whose heart was so hardened that he ignored the desperate cries of his kingdom’s Hebrew slaves. The slaves longed for wholeness, for the easing of their burdensome yolk, but the Pharaoh did not listen to their cries.

The events of that night are now in the past, but there are moments when I’m transported back to that empty square and to the earnest faces of two boys who, upon receiving a simple burger, took to praising God, and to praising me. I’m reminded of them, for example, when I’m in church and hear again the story of a Pharaoh whose heart was so hardened that he ignored the desperate cries of his kingdom’s Hebrew slaves. The slaves longed for wholeness, for the easing of their burdensome yolk, but the Pharaoh did not listen to their cries.

The story of Pharaoh reminds me of the two boys not only because both events were set in Egypt but also because, in the Pharaoh, I see something of myself. The imperfect heart, which so often fails to incline itself to the cries of those around us, isn’t just a problem for ancient kings; it is a chronic ailment of the human condition. Similarly, the ones who cry for help are not just ancient slaves found in the pages of a book; they are people we stumble upon even in the routine of our lives.

And this is why, five years later, I still pray God’s blessings upon the two boys. I pray as sincerely as they had prayed for me, remembering that while they had nothing material to give, they had given me something greater: an awareness of my spiritual poverty, and a desire for a softer heart.

Cairo Boy photo by Madmonk

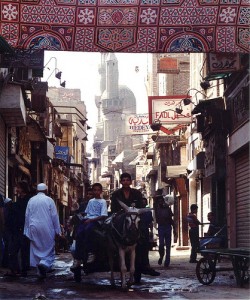

Cairo Street Scene photo by martnpro

* * * * *

Joel Carillet, a freelance writer and photographer, is the author of 30 Reasons to Travel: Photographs and Reflections from Southeast Asia. His work has appeared in numerous publications, including several Travelers’ Tales anthologies, the Christian Science Monitor, and WorldHum. Visit Joel Carillet’s website to learn more about his writing and photography, or to check out his weekly photoblog.