By Beth Malone

When we finally arrive, there is a spider the size of my ear clinging to the ceiling. I glance at my two friends beside me; one look tells me neither has the courage to climb on the bed with a rolled-up magazine. As for me, I’m not just afraid of spiders; I have certified arachnophobia. As panic renders me motionless, all I can think is, “What am I doing here, anyway?”

When we finally arrive, there is a spider the size of my ear clinging to the ceiling. I glance at my two friends beside me; one look tells me neither has the courage to climb on the bed with a rolled-up magazine. As for me, I’m not just afraid of spiders; I have certified arachnophobia. As panic renders me motionless, all I can think is, “What am I doing here, anyway?”

At that moment, one of our hosts, D.J., knocks to see if we need anything. We jump on his offer.

“Can you please get the spider for us?” I beg.

“What, that one?” he asks, pointing.

“Yes, yes, that one! Please!”

D.J. just smiles. Cool as cream pie, he reaches up and smashes the spider with his bare hand while we scream and dive for the opposite end of the room. Plucking the spider’s body between forefinger and thumb, D.J. holds it out to us, his grin spreading as we cower in the corner.

“He won’t hurt you,” he says. “Do not fear.”

Do not fear: A phrase for angels and adrenaline addicts, and I am neither. I was raised by parents who consider things like aspartame and cell phones to be potentially deadly. Growing up, I learned to calculate risk by counting on the worst-case scenario. So I avoided roller coasters, wakeboarding, and motorcycles. In my mind, sports resulted in injury; public speaking, in death by tomatoes; opportunity, in failure. It was probably better to just stay home and read a book.

As I became an adult, my cautiousness morphed into chronic anxiety, which in turn led to insomnia, depression and lung-crushing panic attacks. During the last few years, my life had hit a stormy season, sending one wave crashing right after the other: job loss, major move, husband’s career change, major move, chronic sickness, another move. The constant uncertainty, the half-unpacked suitcases, the clicking through job listings at three in the morning: I let it all chip away at me like a jackhammer. I felt fragile, raw to the touch.

As I became an adult, my cautiousness morphed into chronic anxiety, which in turn led to insomnia, depression and lung-crushing panic attacks. During the last few years, my life had hit a stormy season, sending one wave crashing right after the other: job loss, major move, husband’s career change, major move, chronic sickness, another move. The constant uncertainty, the half-unpacked suitcases, the clicking through job listings at three in the morning: I let it all chip away at me like a jackhammer. I felt fragile, raw to the touch.

My husband–a man who never tested the waters before back flipping into them–suggested the trip. Two weeks, with two of my best friends, anywhere in the world. It wasn’t hard to talk them into it. After all, what could beat lying on a warm beach with a cold drink beside your two best friends? We surfed travel web sites and began to dream of bicycle rides, castles and red wine in the Spanish countryside.

Then, something very mundane happened: The three of us received a link to a blog. It was by an American woman who moved to Uganda right after high school and adopted–get this–14 children. All by herself.

I stayed up for hours one night reading her archives, gaping at her pictures. She was only twenty-one years old. She spent her days driving a van around the city, looking for people to feed or children to treat for various illnesses. It was as though her words broke my heart like pottery, swept it into a pile, and left it beating. In the morning, I sent an e-mail to my friends. I didn’t want to go to Spain anymore.

Turned out, neither did they.

So, after a few phone calls and several dozen e-mails, the three of us end up in Kyangwali, a refugee settlement in western Uganda. We don’t even know what we’re hoping to accomplish. We aren’t engineers or architects or borderless doctors. We’re just, well, willing.

So, after a few phone calls and several dozen e-mails, the three of us end up in Kyangwali, a refugee settlement in western Uganda. We don’t even know what we’re hoping to accomplish. We aren’t engineers or architects or borderless doctors. We’re just, well, willing.

But to be honest, my willingness confuses me. I don’t know exactly what it was that urged me onto that plane. I can’t figure it out, exactly, until I get there.

The road to Kyangwali is so bad I’m sure we’re going to bury the nose of our car in a muddy ditch and have to limp away. Our driver, however, is cheerful.

“You’re lucky you’re here at a good time,” he says. “During rainy season, you can get stuck for hours.” We lurch into another pit, and I try not to lose my lunch.

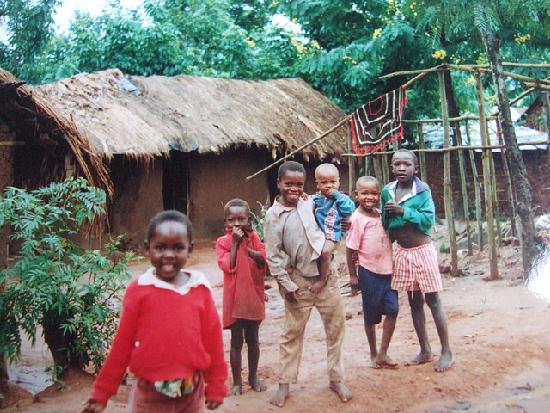

I’m having a hard time believing that just two days ago, I was cruising down a freeway, passing hotels and fast food joints on my way to visit my parents in their three-story home. Outside the window, I see hundreds of mud huts, barefoot children and people carrying enormous bundles of firewood on their heads.

“These people have been here my whole life,” I think. I can’t believe I’ve spent a lifetime never knowing that this place existed.

We pull up to the primary school where we’re staying, and our hosts–residents of the camp and members of an organization called Coburwas–greet us with potato stew. We crowd around a rough table beneath the single bare bulb hanging from the ceiling.

After the poverty we’ve already seen, I expect a somber mood to permeate the room. I’m wrong. Benson imitates and exaggerates an American accent: “Hey guyyyyyssss! WhasSUP?” Bridget sticks a comb in her hair, crosses her arms, and poses for pictures. D.J. spontaneously busts out rapping. They never stop smiling. I can’t help but be disarmed by it.

After the poverty we’ve already seen, I expect a somber mood to permeate the room. I’m wrong. Benson imitates and exaggerates an American accent: “Hey guyyyyyssss! WhasSUP?” Bridget sticks a comb in her hair, crosses her arms, and poses for pictures. D.J. spontaneously busts out rapping. They never stop smiling. I can’t help but be disarmed by it.

And every day following, that phrase comes up: “Do not fear,” John tells us as we hack through the jungle on our way to the sugar-cane fields, eyes peeled for pythons. “Do not fear,” Celestin says as our jeep slides sideways into a slick-as-nose-grease mud pit. “Do not fear,” Eric laughs as we nearly walk right into a herd of cattle one pitch-black night.

“Aren’t you afraid of anything?” I ask John one night. He just smiles.

“Even if I see a lion there,” he says, gesturing to the school building 20 feet away, “I cannot fear. I will take my machete and chase it away. There is no way I can fear it.”

I raise my eyebrows. I would back off if it were only a stray cat.

John, like the other members of Coburwas, is too busy to fear. Too busy raising money for the school, or digging wells for clean water, or organizing seminars on leadership. When we ask, our new friends talk about escaping the Congo, sometimes after seeing rebels hack their family members to death with machetes. Then invariably the conversation turns to community action. They talk about becoming doctors, lawyers, social workers–they want education to pry the community from the jaws of suffering. They see living in the past as counter-productive.

“The future is now,” they say over and over.

I cannot fathom how these people choose not to dwell on the past, and how they stare unflinching at the future. I wonder how they balance so precariously on hope, the tower between the twin chasms of despair and fear.

I cannot fathom how these people choose not to dwell on the past, and how they stare unflinching at the future. I wonder how they balance so precariously on hope, the tower between the twin chasms of despair and fear.

On Sunday, we attend their church, a tin-roofed building with flowers strung from the rafters. We pack onto the benches. Everyone’s bodies touch; it’s like you can feel the pulse of the entire crowd on your skin. A crowd of teenagers sings at the top of their lungs, shuffling their feet and shaking their shoulders. It goes on for hours, so that my ears ring and my heart feels like a full bucket. When it ends, they begin to pray. Hard.

Three women stand and pray that their crops will come in. If the sun beats too hot, if the rain comes too hard or not at all, if the seeds don’t sprout, if God does not come through, they’ll starve. They stand and sway and cry, banging on heaven’s door.

When prayers are over, announcements begin.

Then I witness a miracle.

The pastor tells the congregation about an outreach the church has planned for that week. And the women raise their hands and volunteer to bring bags of rice and beans to feed the crowd that will come.

I watch as they reach their hands high in the air. I can see their eyes shining. The whole room reverberates with their decision; I can feel it pass through my body like an electric shock.

I watch as they reach their hands high in the air. I can see their eyes shining. The whole room reverberates with their decision; I can feel it pass through my body like an electric shock.

This is the moment I realize that fear cannot co-exist with love. Fear, like love, takes energy, thought, planning, and permission to live inside a person. But love is a flood that washes fear away. Even a small amount of love can make you jump on a plane bound for Africa. And a huge amount of love can make you give everything–all you have to live on–to someone you may not even know.These women feel the blistering heat of fear and extinguish it like they’re dumping buckets of water onto a flame. They will not give fear room to burn here.It is then that I realize I have that choice too, every single day.

*****

Beth Malone writes, mothers, and teaches English to refugees in Colorado, where she lives with her daughter and husband. To find out more about the refugees in Kyangwali, please visit Coburwas or Think Humanity.

*****

Photo credits:

Uganda Girls: SuSanA Secretariat

Spider: Mario

Uganda Kids: K. Kendall

Ugandan Women Fruit Vendors: US Army Africa

Ugandan Passionate Worship and Prayer: Mac Mitchell

Volunteers with Ugandan women: Shared Interest