By Astrid Vinje

“Rachel, can I ask you something?” I said.

“Rachel, can I ask you something?” I said.

We were walking out of her family compound one warm and calm night in May. It was my second year of being a Peace Corps volunteer in the tiny West African country of Togo, and I was in the regional capital, Sokod, to do some work with the local organizations in the city. Rachel, a close friend, had invited me to come over and have dinner with her family while I was in town. She had prepared my favorite West African dish, fufu, consisting of pounded boiled yams with a special tomato and mushroom sauce, and had spent hours getting the dish just right. Now, after a filling meal and good conversation, she and her sister-in-law were escorting me back to the volunteer transit house, a short five minute walk from her family compound.

“Yes, of course,” she replied, responding to my question.

“Do you like being a mother?” I asked.

Rachel had just given birth to her second child, Yazid, about a month ago and was still taking some time off from work. Although she was already as active as ever, her body still bore the signs of the pregnancy. Full hips and breasts, the curves of an hourglass, so common among the women of Africa.

“I love being a mother,” she answered, “it’s the most amazing thing to experience.”

“I love being a mother,” she answered, “it’s the most amazing thing to experience.”

I glanced over in her direction. It was difficult to see in the darkness as there were no streetlights along the road. The only light came from the moon and an occasional lantern or light bulb from the cement-walled compounds we passed. We walked along the dirt road to the transit house, trying to avoid the rocks and ditches that jutted and dipped along the path. Nighttime in Togo was a different world. The innocent and benign suddenly became menacing and mysterious, made more so by the pale glow of the moon. Yet even in the dimness of moonlight I could see her beaming as she talked.

“It’s what gives my life purpose,” she continued. She smiled and gave a soft giggle.

I suddenly thought of my sister in the states, whose baby was due in June. We were only a year and a half apart, and already our lives had diverged so much. I had chosen the uncertainty of pursuing a career, and she had chosen the security of settling down with a family. No doubt, she would have responded the same way. I wondered if it was society telling her to feel this way, or something inherent in being a woman.

“You’ll understand too, A’cha,” Rachel said, calling me by my local name, “once you become a mother.”

She said this in a way as if to assume that all women will someday become mothers. I tried to picture myself as one. Driving my children to soccer practice, ballet recitals and after-school activities. Devoting my time and my passions to their needs and whims. A part of me did want that experience, the fulfillment that comes with being a parent. But there was still so much of life that I wanted to live, and I was not ready to give up my selfish wanderlust for another human being.

My mind flooded with the thoughts of how difficult it was to have both a family and a career. Can women really have it all? I wondered. In this day and age, the idea of a successful woman is one who can balance the societal obligations of raising children and the expectations of pursuing a career. A precarious juggling act of modernity and tradition, all done with perfect poise, ruby red lipstick, shining pearl necklace, and a winning smile. This was always something I kept coming back to, the conflict between ambition and family. Any woman who chose one over the other, or failed to do both successfully seemed to be automatically deemed a failure.

My mind flooded with the thoughts of how difficult it was to have both a family and a career. Can women really have it all? I wondered. In this day and age, the idea of a successful woman is one who can balance the societal obligations of raising children and the expectations of pursuing a career. A precarious juggling act of modernity and tradition, all done with perfect poise, ruby red lipstick, shining pearl necklace, and a winning smile. This was always something I kept coming back to, the conflict between ambition and family. Any woman who chose one over the other, or failed to do both successfully seemed to be automatically deemed a failure.

“It’s hard sometimes,” I said, “I do want to have a family of my own, but I also want to work first.”

“I know,” replied Rachel, “it’s very difficult.”

“You have to find a balance between the two,” I continued, “having a career or having a family. It’s like you have to sacrifice one thing for the other.”

“Yes, yes,” she agreed, “it’s exactly like that.”

“It’s nice that you have Mohamed,” I said, thinking of her husband, “I mean, most men here aren’t very supportive of their wives at all, but Mohamed seems different.”

We continued talking, walking past mosques and family-run stores, our path along the bumpy dirt road illuminated by Rachel’s flashlight. Her sister-in-law, Mohamed’s older sister who was visiting from one of the nearby villages, walked quietly beside us. She knew little French, and spoke mostly Cotokoli, the language of the local ethnic group. I guessed that she only had a second grade education, if any. As Rachel and I conversed, she would interrupt from time to time to ask me to take her to America. She had no idea what we were talking about, but seemed content with simply walking with us. It seemed strange to see these two women together, so different from each other. One so obviously ahead of her time, and the other stuck in the role that her culture had laid out for her.

Compared to most Togolese women, Rachel was an exception. Even compared to American women she would stand out. The president of a small non-governmental organization in Sokod, Rachel was one of the few Togolese women I knew who actually held a university degree, something that even a lot of men didn’t have in Togo. Her organization was very active in the community, developing projects and peer educator trainings for school children in surrounding villages. Rachel had a great love for children, and her life goal, as well as her organization’s goal, was to ensure that all children had the opportunity to go to school and get an education. This young woman had more ambition than many women I knew back in the states.

Compared to most Togolese women, Rachel was an exception. Even compared to American women she would stand out. The president of a small non-governmental organization in Sokod, Rachel was one of the few Togolese women I knew who actually held a university degree, something that even a lot of men didn’t have in Togo. Her organization was very active in the community, developing projects and peer educator trainings for school children in surrounding villages. Rachel had a great love for children, and her life goal, as well as her organization’s goal, was to ensure that all children had the opportunity to go to school and get an education. This young woman had more ambition than many women I knew back in the states.

We were similar in age, but it seemed as if she had already accomplished so much more. In a country where the average woman has less than an elementary school education, it was downright amazing. Rachel was opinionated, she was passionate, and she was married to a man who truly respected her and supported her in everything she did. For the majority of women in Togo, whose lives were dominated by the responsibilities of feeding a family of five or more kids, the burdens of being in charge of all the household chores like cooking, cleaning, carrying water and doing laundry all by hand, the stress of making ends meet by selling goods at the march, and the humility of having to submit to a husband who saw them as little more than a mother to their children, Rachel was an inspiration and a role model. Yet, even she replied that it was motherhood that gave her life purpose, rather than her accomplishments in work or education.

It made me wonder again, is it culture that makes us feel this way, or is it something that naturally comes from being a woman? Is it because all girls, regardless of culture, have been socialized since birth to want to have children that motherhood holds such a significant place in our lives? More so, it seemed, than for men? I thought of all the mothers-to-be who came to the pre-natal consultations every week at the health clinic in my village. All the births I had seen there. Language barriers kept me from saying anything more than “Congratulations,” but I’m sure if asked, they would reply with a similar answer.

It made me wonder again, is it culture that makes us feel this way, or is it something that naturally comes from being a woman? Is it because all girls, regardless of culture, have been socialized since birth to want to have children that motherhood holds such a significant place in our lives? More so, it seemed, than for men? I thought of all the mothers-to-be who came to the pre-natal consultations every week at the health clinic in my village. All the births I had seen there. Language barriers kept me from saying anything more than “Congratulations,” but I’m sure if asked, they would reply with a similar answer.

“Men have it easy,” I said, after a moment’s pause.

“They do,” Rachel agreed, “when they have children, they don’t have to worry about having to take care of them, having to feed them, or stopping work to have them.”

I told her how in the states, the fathers played more active roles in raising their children. I explained how many fathers accompanied women to birthing classes, how they were present in the birth, and how they often helped in taking care of the infant, even if they weren’t married to the mothers. It was a stark contrast to the role of the father in Togo. I never saw any men come with the women to the pre-natal consultations, and rarely saw them helping their wives when they were in labor. There were only a few men in Togo that I knew who cared at all about the welfare of their wives and children beyond the point of what was necessary. Mohamed was one of them.

“You see?” she said, “Men here just let the women do all the work!”

“But Mohamed is different, right?” I asked.

“Oh yes,” she replied with a laugh, “Mohamed is different.”

I wondered whether there would ever be a day when women like Rachel would cease to be the exception and start being the norm here in Togo. For the moment, it seemed like a long way off. I thought of the women in my village, still relegated to minimal roles in village politics and development. I thought about Rachel’s sister-in-law, whose lack of formal education allowed her to only see me as a ticket out. For the moment, there was still a lot of work to be done. Both in Togo and in the US, women must struggle to find a balance between motherhood and career as a means to define who they are.

I wondered whether there would ever be a day when women like Rachel would cease to be the exception and start being the norm here in Togo. For the moment, it seemed like a long way off. I thought of the women in my village, still relegated to minimal roles in village politics and development. I thought about Rachel’s sister-in-law, whose lack of formal education allowed her to only see me as a ticket out. For the moment, there was still a lot of work to be done. Both in Togo and in the US, women must struggle to find a balance between motherhood and career as a means to define who they are.

I sighed as we continued on our way. Around us I could hear the sounds of fufu being pounded by women on the huge wooden mortars and pestles, accompanied by the clanging of heavy cooking pots called marmites being taken out or put away. The radio played a popular song from Côte d’Ivoire. A motorcycle sped by, the glow of its headlight and the hum of its motor the only evidence of its existence in the darkness. The sounds of the night surrounded us, a simple soundtrack to our evening stroll. One day, I thought, one day.

*****

Astrid Vinje’s travel stories can be found on the travel sites, OnAJunket.com and BootsnAll.com. Her fiction work has been published in quiet Shorts, a literary magazine based in Seatle, WA. For more of her writings, visit The Wandering Daughter.

*****

Photo credits:

Togo Woman: Amanda

African Mother and Child: hdptcar

African Mothers and Babies: hdptcar

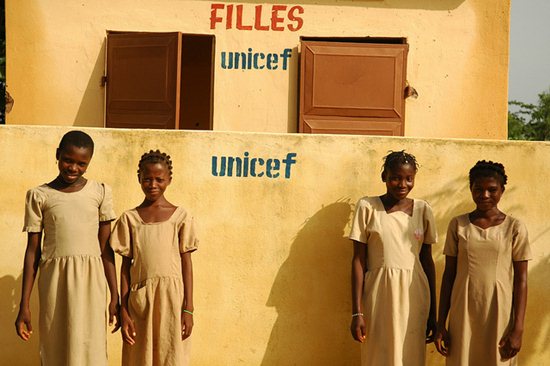

Togo Girls: The Co-operative

Woman at Northern Togo: David Bacon

Togo Women Making Fufu: photos fantastiques