One of my top priorities on my first visit to Oaxaca, Mexico was to make sure to visit a Cochineal Farm. I had been vaguely aware of cochineal for some time and knew if by one of its other names, carmine. I learned more about it when I became a docent at my local art museum and discovered its use in paint and dye. And later still, our docent’s book club read the book A Perfect Red: Empire, Espionage, And the Quest for the Color of Desire by Amy Butler Greenfield which explores in depth the history and allure of cochineal. After that kind of build up, I couldn’t visit the historical center of cochineal in the world and not go meet cochineal in person.

As early at the 14th century, cochineal was being harvested by the Aztecs and Mayans to be used as a dye. Cochineal are small bugs that have a concentration of carminic acid in their bodies as a natural defense to predators as it makes them taste bad. Birds, ants, rats and even innocent looking lady bugs still enjoy eating cochineal, so there are plenty of threats in their environment. They are also a particularly finicky insect that only like to feed on one kind of cacti, the nopal, and thrive in specific climate conditions of heat, sun and humidity. It turns out, their preferred climate is exactly what is offered around Oaxaca, Mexico.

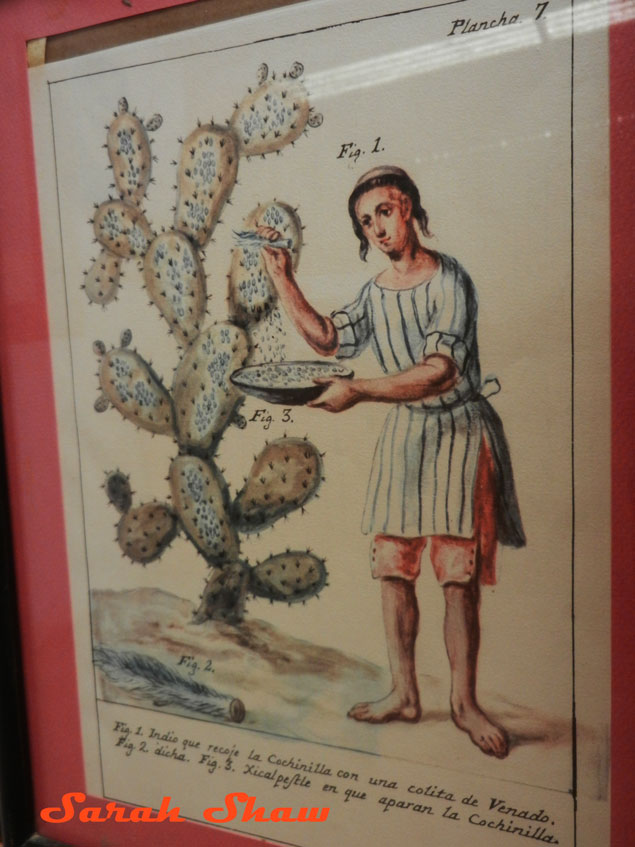

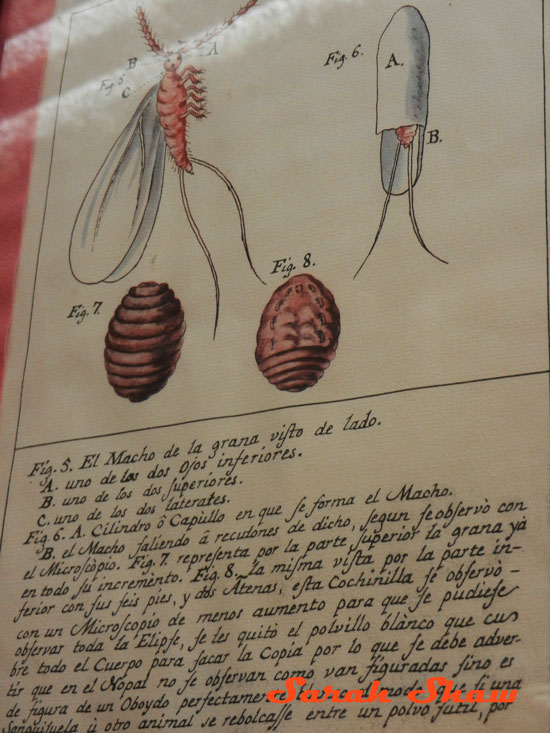

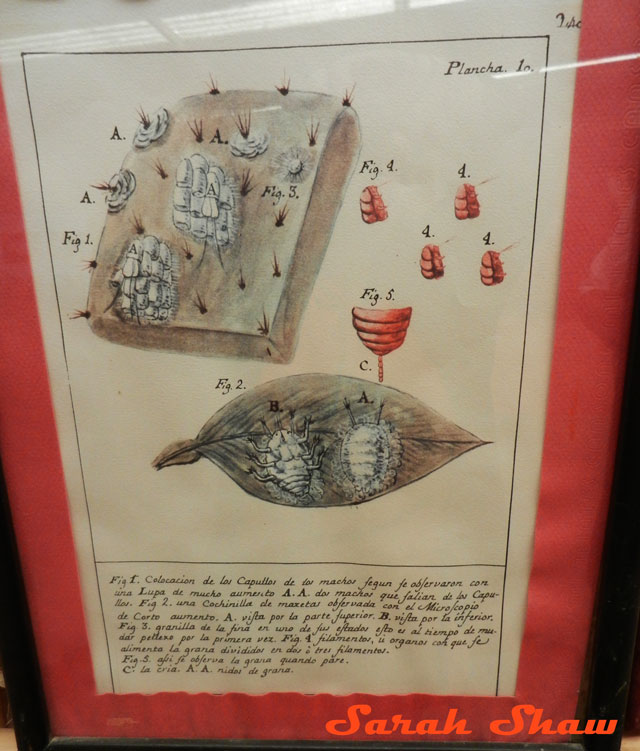

Cochineal are a seemingly insignificant bug by appearance. The color is harvested only from females and eggs. The wingless females average around 5 mm long. The males are even smaller but have wings for use in finding their mates. Interestingly, the males only function when mature is to mate as by that time they lack the ability to eat and they die shortly after fulfilling their procreational duties. Because of their size and short life span, it is rare to spot male cochineal. The females on the other hand have all the glory in the cochineal family. They park themselves on the nopal cactus arm of their choice, stick their beak like mouth into the cactus and suck away at its nutrients. After they have bred, they give birth to immature cochineal known as nymphs or crawlers.

Cochineal nymphs also are very fond of nopal cactus and gorge themselves on the same leaf where they were born. They excrete a white, mold looking substance that provides a layer of protection from the sun and covers them just like a lace shawl. They feast away until ready to move on to a replenished table on a new nopal leaf. Nymphs move to the edge, let the wind catch their self made parachute and fly over to the next destination. And so the cycle begins again.

As I mentioned earlier, the Mayans and the Aztecs both learned early on about the deep red cochineal could produce for them. Female cochineal and their eggs would be scraped off a nopal cactus leaf and added to a boiling pot of water to kill all the bugs. The cooked cochineal would then be laid out to dry and dehydrate. They take on an appearance of a purpleish-red vermiculite and can be stored easily until ready for use as a dye. In this state cochineal, or grana cochinilla, is also easy to trade and ready to travel the world. The stage has been set and from curtain right, enter the colonial powers.

Europe was color hungry as the colonial powers began to test their naval dominance and conquer the world. Most of the cloth being woven and made available to the people of Europe was a boring palette of browns. Only royalty, the clergy and a few wealthy merchants had the money or access to finer cloths like silk and brilliant colors that were starting to return on ships from exploration. When you think of kings, you may often picture them in robes of rich reds. I see cardinals in the Catholic church in those same colors in my mind. Those reds came from cochineal. As the Spanish, Dutch, French, English, Portuguese all fought for superiority on the seas, their monarchs craved more and more red for their wardrobes. Each monarchy wanted to be attired in the very best the world had to offer and it had better be finer than their neighbors.

When cochineal was discovered in Mexico, a frenzy took place to find the secret of how each country could control their own supply of cochineal. Monarchies all jockeyed to get to Oaxaca and steal some bugs to take back to their own greenhouses and conservatories. Elaborate and ridiculous schemes and spy missions were launched and some even successfully sneaked cochineal out of Mexico. Yet time after time, they failed. The bugs would fail to thrive and eventually die no matter what was tried. Spain was in control of Mexico by this time and they also were setting the price for red on the European market. This brilliant and color fast red was required everywhere and was being traded even with India. For a long time, cochineal was Mexico’s second most lucrative export with silver being the only thing valued more.

As time passed, scientists and dyers spurred on by the promise of riches and fame, discovered other ways to create the color red for cloth. Synthetic dyes were invented that also offered brilliant and color fast reds that did not require trade with Spain. And slowly over time, cochineal was mostly forgotten. The people of the Oaxaca Valley continued to nurture their once famous bug. To them all along, it was their source for red and many other color variations, important to their own garment and textile production. So on a small scale, cochineal was once again produced to please the local inhabitants. And where it can be found today, in the form of the cochineal farm I visited.

Recently there has been a resurgence in interest in cochineal. Bad things have been associated with synthetic dyes, red in particular. You may remember the cancer scares connected to some red dyes. People are also discovering that they have sensitivities to synthetic dyes that don’t exist for them with natural dyes. There has also been a movement to return to a slow and simple lifestyle. In food production, more and more people seek organic, natural edibles and want artificial colors removed from their dinner tables. There is also an interest in natural, organic make-up for women. Slowly and quietly, cochineal is once again becoming king.

And so my guide Raul and I sought out to find the cochineal farm, Rancho La Nopalera, outside of Oaxaca City one afternoon after a morning of visiting other sites. I found the cochineal production to be taking place in special greenhouses enclosed in some sections with netting instead of glass. This was as much to keep the cochineal in place as it was to protect them from predators. Giant wooden trays were built that held row after row of nopal cactus leaves with their base stuck in the dirt. Each nopal leaf looked a little like a green mitten with bits of mold on it. Some trays were covered with additional netting to keep its brood in place. Others were far enough along in their development that they were entirely open to the air. Each flat was marked with the date that eggs had been laid and the cochineal nursery, or nopalry, waited its time till harvest. As you walked through the greenhouse, you could observe cochineal in all states of the cycle as it was a continuous process allowed by the consistent climate in Oaxaca.

Rancho La Nopalera also has a small museum and gift shop (yes!) on its grounds. In the museum, many exhibits are set up to allow you to walk yourself through in case one of the employees at the ranch is unavailable to join you. The history of cochineal is explored as well as exhibits that show the current methods used to grow and harvest cochineal. Another section will show you its use in local textiles. You will end your time by going on to the next building where a modest gift shop offers a variety of cochineal related products. You can buy bags of dried cochineal, as I did, which you can take home with you to create your own dyes. I also purchased a small bottle of cochineal ink which can be used for writing or painting. A selection of woven items were offered made from cochineal dyed fibers as were the yarns themselves. There was a small collection of cochineal based cosmetics including lipstick and rouge. You could also purchase some candies where carmine had been used as a food dye.

And that brings us to the cochineal resurgence and that the inclusion of cochineal in products which may come as a surprise to many people. Cochineal created carmine, is valued as a food dye and as a stain in cosmetics. It may be listed by other names such as calcium carmine, ammonium carmine, cochineal extract, crimson lake, natural red 4, C.I. 75470, E120 or even just “natural dye.” You are likely to find cochineal in food products that have a red color to them including alcohol, candies, cookies, jams, juices and cheeses. In some countries, though not allowed in the U.S., carmine may be injected into meat to make it appear more appetizing. Drug companies use cochineal to color their pills red. Cosmetic companies consider it safe for the face and near the eyes so it may be in blush, lipstick, face powders and even eye shadow. Many vegetarians as well as people whose religion requires special dietary observance may be surprised to learn of cochineal being included in products they use every day.

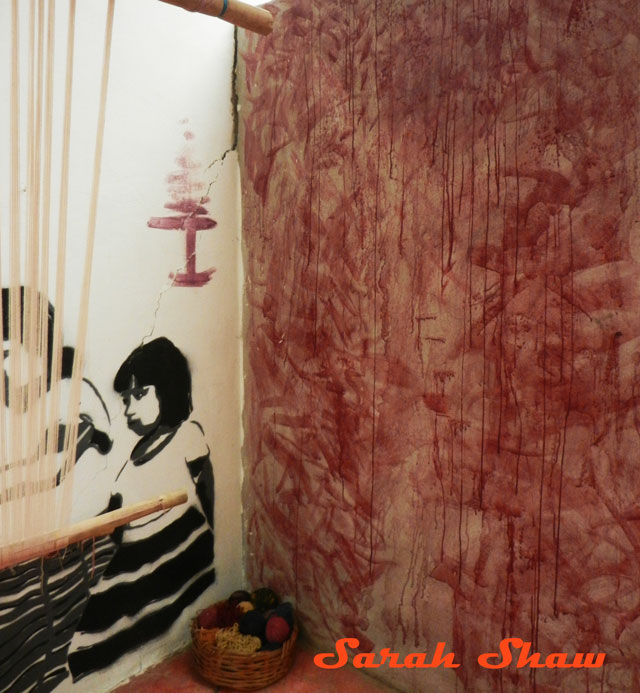

Coming back to Oaxaca, Mexico, we find cochineal at use as its always been. Local artisans use it to dye the cotton and wool they use to weave fabric for clothing and textiles for blankets, pillows and rugs. Their creations are both for personal use as well as sale to their neighbors and the tourists who readily purchase their weavings as meaningful souvenirs. During my time with Raul, I also visited a studio of artists who carve and paint alebrije, the mythical wooden creatures so popular with collectors. Their elite collection are all designed with natural based paints including those made with cochineal. We also visited a weavers co-operative where they frequently weave with cochineal dyed fibers. Please click on the links to read my posts about these Oaxacan artisans.

Coming back to Oaxaca, Mexico, we find cochineal at use as its always been. Local artisans use it to dye the cotton and wool they use to weave fabric for clothing and textiles for blankets, pillows and rugs. Their creations are both for personal use as well as sale to their neighbors and the tourists who readily purchase their weavings as meaningful souvenirs. During my time with Raul, I also visited a studio of artists who carve and paint alebrije, the mythical wooden creatures so popular with collectors. Their elite collection are all designed with natural based paints including those made with cochineal. We also visited a weavers co-operative where they frequently weave with cochineal dyed fibers. Please click on the links to read my posts about these Oaxacan artisans.

Cochineal does produce a vibrant color of red that has been valued around the world and through the centuries. Other colors are also derived from cochineal. Mix lemon juice in with it, and suddenly you have a bright orange. Instead add a little baking soda, and a brilliant purple appears. Natural dyes are a fun way to inspire any junior chemist. At the weavers cooperative, he showed me how you could continue to add or subtract different substances from the mixture to gain 46 different, distinct shades just from cochineal. You can see how an artist could be inspired to create. One of the rugs I brought home was dyed completely with cochineal although it displayed many colors in addition to red.

If you are interested in learning more about cochineal, the absolute best thing you could do would be to visit the Rancho La Nopalera with Raul. You can reach him with the contact information listed below. He can also help you to see all the other sites and attractions throughout Oaxaca. You may also want to read A Perfect Red: Empire, Espionage, and the Quest for the Color of Desire for an interesting and thorough telling of cochineal’s history. While searching Etsy for cochineal products, of which there is a nice selection of textiles as well as dyes and inks, I met a weaver who works with cochineal for her own natural dyes and fibers. She shared with me an Oaxaca Natural Dyes Secrets Workshop being held in Teotitlan del Valle (the village where I visited the weavers cooperative) this January. That workshop sounds like a dream and I am extremely tempted to sign up for it!

Contact Raul Felix to tour Oaxaca:

Mobile (951) 135 69 97

Home (951) 144 36 37

Email: [email protected]

Have you ever worked with natural dyes? Do you own any items colored with cochineal? How do you feel about manufacturers adding cochineal to your food, cosmetics or medicines and listing it as a “natural dye?” I’d love to hear your thoughts and experiences.

Until we shop again,

Sarah