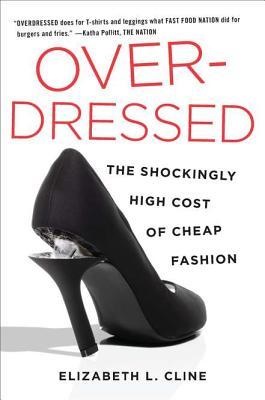

I’d wanted to read Elizabeth L. Cline’s Overdressed since I read this excerpt at Slate.com. I’ve long hoped that I could do my part to save the planet by using tote bags and shopping at thrift stores. Her book quickly deflates that idea.

And while I’ve resisted goodreads.com because 1. I feel maxed out on social media right now and 2. my love of books gets enough attention at my day job and in conversations with friends, sometimes WanderChic likes to indulge in book talk, especially when the book teaches her something about style. (And according to the twitters, Goodreads just hit 10 million users, so clearly they’re thriving without her).

In Overdressed, Cline shows some consequences of our unbridled consumption. It’s a grim picture, and still, I couldn’t put the book down.

Cline labels herself a recovering “fast fashion junkie.” Before reading her book, I hadn’t realized that the radical changes in the fashion industry, including the rise of fast–and largely disposable–fashion, had occurred in the last 20 years.

I felt like Cline was talking to me, someone who’s also trying to break the habit of fast fashion, who used to frequent the clearance racks at Target and T J Maxx, who was reluctant to pay full price for anything. It’s really been in the last couple of years, like, when I got my big girl job, that I started to shift my shopping to fewer, higher quality items. (I found the sassy ecard, above, on Bridgette Raes’ blog).

I, too, had clung to what Cline calls the “clothing deficit myth,” which she explains as most Americans’ view that “there is another person in their direct vicinity who truly needs and wants all of our unwanted clothes” (127). But so much of our excess clothing ends up in other countries, where it drives down the prices of clothes to the point that local businesses can’t compete. Or it ends up in the landfill: “Every year, Americans throw away 12.7 million tons, or 68 pounds of textiles per person, according to the Environmental Protection Agency,” she reports (122). And far from environmentally neutral, “about half of our wardrobe is now made out of plastic, in the form of polyester” (123).

Cline also considers the human cost, the loss of American jobs to overseas manufacturing and the deplorable conditions of many of those overseas workers. She claims “Garment workers overseas are still only earning about 1 percent of the retail price of the clothing they produce” (159). It’s imperative that we consumers learn more about the production of our clothes and support companies with ethical practices.

Fortunately, Overdressed doesn’t leave us without hope. For Cline, learning to sew is a turning point in her relationship with clothes. In a chapter that includes a description of the Slow Clothes movement, Cline takes sewing classes to repair and customize clothes.

I have a lot to learn about taking better care of my wardrobe and buying better clothes (not just the quality of the garment, but conditions in which it was made.) It’s a baby step, but I googled sewing classes in Spokane, and found The Top Stitch. I’ve passed their store before, but I’ve never been inside. Maybe early next summer, I’ll treat myself to a sewing tutorial. Can I be salvaged as a, gulp, crafter?

Overdressed is a compelling reminder that when I vote with my dollar, it always counts.